Sometime during March 2020—ask him and he’s not exactly sure of the day or even the week—Ed Bastian walked into the conference room near his office on the Atlanta campus of Delta Air Lines and began the process of saving one of the most important corporations in the world.

On the walls around him were satellite photos of the airports around the U.S. served by Delta—including JFK, MSP, DTW, LAX, SEA, BOS, SLC and, of course, dominating the photos of all the others, ATL, the city-size Hartsfield-Jackson airport located just across the road from Bastian’s office. From space, the airports all look eerily empty. And on that day, they nearly were. Amid the fast-spiraling panic of Covid-19, Bastian was presiding over one of the more traumatic meltdowns in global business history. Delta, which enjoyed $47 billion in 2019 revenue, suddenly had “basically nothing” coming in, and worse, millions of customers were cancelling flight reservations, demanding refunds, draining reserves.

As his senior leadership team of 12 assembled in leather-backed conference chairs for what was to become a new daily ritual, an in-person 9 a.m. status meeting, it promised to be yet another session of financial and operational Whac-A-Mole, where numbers ran only red and the essential data points they discussed—about health, about flights, about the status of the outbreak—were often irrelevant as soon as they were uttered.

“Anything you planned, you were wrong by the afternoon,” Bastian recalls now, looking around the conference room during a July interview with Chief Executive. “You were paralyzed by all the information, all of the news. This was a societal thing.”

Bastian hadn’t slept well—who had?—in days. His mother, Mary—“my closest friend”—had died unexpectedly in February, possibly from Covid, and the painful loss was all too fresh. Daily reports about the collapse of the business, worries about safety, about bankruptcy, about layoffs of the team he had hoped never to lay off—it all weighed on Bastian as he fought to contain his mounting fears. Just two months earlier, he’d kicked off the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas with a keynote unveiling a vision for the future of aviation in front of tens of thousands of attendees and the assembled global media. Now all that—and more—was gone.

“I’m starting to think I’m back in the Bible, you know, Job or something,” he says, shaking his head, remembering that time. “You know, what’s coming next? And I’ll be honest, I spent about a week, I felt pretty sorry for myself. All we built was destroyed, and [we’ve] got to go do this again.”

But rather than wallow, he talked to people who knew him well and ruminated on his reaction to events. And then, he decided to see the moment differently: as an opportunity, not a curse. “This was not a time for me to feel sorry for anybody, particularly myself,” he says. “This was a time to lead—the company never needed leadership at the level needed right then and there. It was the most important time to sit in this chair in the near 100-year history of Delta Air Lines. You can say I was burdened to have that, or I was blessed to have that. I chose to believe that I was blessed to have that opportunity. It was a privilege to lead this company to a safe place.”

‘For the Benefit of Us All’

That decision, that choice, is at the heart of one of the more remarkable comeback stories in recent business history. In the three years since the darkest days of the pandemic, Delta Air Lines, born in 1925 as a crop-dusting service in the Southeast U.S., has, under Bastian, once again become the most awarded, sophisticated and technologically advanced airline in America and, arguably, the world, a daily dance of 4,000 flights run by 90,000 employees across every time zone.

That decision, that choice, is at the heart of one of the more remarkable comeback stories in recent business history. In the three years since the darkest days of the pandemic, Delta Air Lines, born in 1925 as a crop-dusting service in the Southeast U.S., has, under Bastian, once again become the most awarded, sophisticated and technologically advanced airline in America and, arguably, the world, a daily dance of 4,000 flights run by 90,000 employees across every time zone.

A mission-driven culture that proved remarkably resilient, as well as key strategic—and somewhat counterintuitive—multibillion-dollar bets on technology and infrastructure placed by Bastian and his leadership team, carried Delta through the pandemic. The company emerged from peril to capture an almost-unfair share of the unexpected resurgence of post-Covid travel that has stuffed airports—and revived Delta’s fortunes. While Delta’s shares have yet to recover to their pre-pandemic highs, they’re at their highest levels since the summer of 2021 and continue to outpace all others in the industry. In its most recent quarter, Delta clocked a 19 percent increase in earnings over the prior year, with operating profit of $3.14 billion for the year so far. The airline has predicted more than $10 billion in free cash flow over the next few years, much of it earmarked for paying down debt and strengthening the company’s balance sheet.

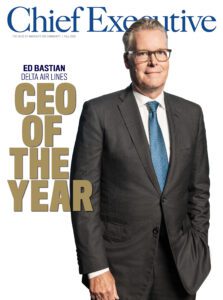

It’s a done-under-duress leadership performance that ranks among the most impressive we’ve seen in the 46-year history of Chief Executive. And it is the key reason this year’s selection committee decided to honor Bastian as CEO of the Year.

“Ed’s leadership-in-action principles and performance created an exceptionally resilient company during very challenging times,” said Tamara Lundgren, chair and CEO of Schnitzer Steel Industries and a longtime member of the selection committee. “His consistent and innovative customer focus, employee engagement and community service set new standards in his industry, and he is an inspiration to the broader business community.”

Added Ken Frazier, the former chair and CEO of Merck and our 2021 CEO of the Year, “Ed Bastian is a true exemplar of what it means to be a visionary, resilient, purpose-driven leader. Nearly all companies were required to make adjustments during the Covid-19 pandemic. Understanding that Delta Air Lines and its people needed to play a pivotal role at the very forefront of this global crisis, Ed confidently guided his organization through a period of unprecedented upheaval and uncertainty to deliver essential services—for the benefit of us all.”

The Delta of Delta

The turnaround in Delta—the Delta of Delta, if you will—was hardly preordained, though the company did have a fair amount of experience with comebacks. There was 9/11, when the nation’s skies emptied along with its airports. In September 2005, there was bankruptcy, the company so poor it couldn’t afford to fix the iconic “Fly Delta Jets” sign that dominates Hartfield-Jackson airport. Bastian was named CFO in the midst of the mess, part of a C-Suite redo that had already seen two other finance chiefs depart in just under 14 months.

Then came the unexpected and unwanted $8 billion takeover offer from US Airways. Bastian and then-CEO Gerald Grinstein convinced employees—who staged huge rallies in Atlanta and elsewhere protesting the deal—to help fight off the approach and prove to creditors that they had the better way. They won and built a bond between management and labor (despite an ugly battle between then-CEO Richard Anderson and the flight attendants union in 2010) that helped restore the company’s fortunes.

When Anderson left in 2016, Bastian, to the surprise of pretty much no one at the airline, was named CEO. He was tested, liked, and he knew numbers. The son of a dentist from Poughkeepsie, New York, his upbringing was ample preparation for a life of challenge and service. Bastian’s father died when he was just 52, leaving Bastian, the eldest of nine siblings, and his mother—his role model—to keep the family going. Despite the burdens, “she was involved in the community, whether it was in the church, the nursing home down the street,” Bastian told Chief Executive in 2021. “She’d bring food every single week to people who didn’t have [enough] and was constantly baking and doing things for others. Her constant engagement in the community giving back was really remarkable.”

He carried that ethic into his career. After graduating from St. Bonaventure in upstate New York in 1979, he started as an auditor at PwC, where he uncovered a $50 million fraud at Madison Avenue ad titan J. Walter Thompson, prompting an SEC investigation that left many PwC executives with marred careers. He was named partner by the time he was 31 but left to join PepsiCo to manage international finances for Frito-Lay. In 1998, he joined Delta as VP, finance and controller.

Then, in 2004, he left Delta to become CFO of Acuity Brands. But surprisingly—who would go back to that mess?—he returned six months later at Grinstein’s request to help save the company. There was just something about Delta he couldn’t shake.

After being named CEO on May 2, 2016, Bastian helped turn Delta into the most profitable airline in the business. Focusing on customer service enabled by big bets on technology, the airline dropped its cancellation rate to under 1 percent by 2018, with only 55 flights scrubbed because of maintenance problems. It grabbed the number-one slot on The Wall Street Journal’s prestigious Best and Worst Airlines list. Shares that traded around $43 when Bastian took over traded near $52, a huge win in the fickle airline business, and performance enough to attract Warren Buffett as an investor, despite his usual distaste for the industry.

In 2019, Bastian and his team grew their lead, sidestepping the grounding of Boeing’s 737 MAX (Delta didn’t have the troubled aircraft in its fleet), which hurt the operations of rivals while demand for travel soared—a record 162.3 million passengers flew Delta that year. A good measure of Delta’s success: The company’s employee profit-sharing program paid out $1.6 billion in 2019—nearly two months of additional pay for each employee. By early 2020, as Bastian took the stage at CES, the company had more than $6 billion in pre-bookings on its balance sheet. Delta looked unassailable.

The Pandemic Plan

It was, of course, not to last. Within weeks, Covid-19 had destroyed the company’s fortunes, and likely its future. But Bastian and his leadership team fought back, using the most powerful tool—maybe the only tool—at their disposal: the banked trust they’d built up with their stakeholders.

From their conference room in Atlanta, Bastian’s team convinced 50,000 employees to take a voluntary leave of absence and 18,000 more employees to depart through a voluntary package, allowing the company to avoid mass layoffs even as rival airlines were furloughing tens of thousands of workers. Delta’s reservation agents—many operating from desks six feet apart in the company’s flight museum, under the wings of a mothballed Boeing 767 called The Spirit of Delta—convinced millions of customers to take vouchers for future travel instead of cash, even when that future was undefined and frightening. In April, Delta and other airlines came together to ask Washington lawmakers to help airlines facing massive furloughs. Delta received $5.4 billion—including a $1.6 billion loan and warrants for 1 percent of the company’s outstanding shares—from the government’s $25 billion overall aid package to the imploding industry. Taken together, it saved Delta, stumbling but alive, to continue operations and begin rebuilding.

They did. They kept flying—every route, as required under the terms of Washington’s aid package—ferrying nurses, doctors, executives and other essential personnel who did not have the option of working from home even as the virus was killing hundreds of people every day. Some 55 million passengers flew Delta in 2020 amid the worst of the pandemic—nowhere near where it had been, but still surprising, given where the world was at the time.

It was an impossibly difficult situation, but slowly, month by month, passengers were reassured that it was okay to fly by Delta’s safety efforts and Bastian’s unending media appearances as the go-to spokesperson for the industry. There were setbacks—including the unfortunately named “Delta” variant. But over the next two challenging years, including the shock and pain of the George Floyd murder, which rocked Delta’s employee base and set off wrenching soul-searching about race and inclusion within the company (which Bastian led personally), and a high-profile brawl with Georgia Governor Brian Kemp over a controversial voting law, they kept at it. They put their digital operations in the cloud for the first time, introduced the concept of free in-air Wi-Fi (on upgraded systems that worked), revamped their consumer app, hired 25,000 new employees as demand rose and finished a much-needed $4 billion terminal upgrade at LaGuardia airport ahead of schedule, among other projects.

Travel soon surged, and Delta was ready. In Q1 2022, the company clocked a $784 million loss. In Q1 2023, it recovered to post a pretax profit of $217 million. By Q2 2023, the number had swung to record revenue and pretax income of $2.2 billion. The company expects to serve nearly 200 million passengers this year—a new record and a whiplash turnaround, Bastian says, that “by far has been the most difficult part of this journey.” Case in point: The bumpy recent revision of Delta’s Sky Miles loyalty program that forced Bastian to admit they’d “moved too fast” and alienated customers.

None of which changes his perspective, gleaned from the toughest days of the pandemic. “I looked at it as an honor to be in here,” he says, sitting at the conference table where so much of the company’s history was made in the past three years. “And I looked at it as a privilege to have that responsibility, to kind of navigate safekeeping for 100,000 employees and hundreds of millions of customers and everything that we do…. It helped me just communicate to our team the importance of what we’re doing.” We talked with Bastian about that time, about what he learned, and what he’ll keep for the long run. The following conversation was edited for length and clarity.

When you see your revenue go to zero, and you have all these people relying on you, what runs through your head when you wake up in the morning and have to confront “What am I going do?”

We were at a period for, gosh, a good 90 days where it wasn’t even zero. It was below zero because we had everybody who had booked tickets in advance wanting their money back. So, not only did we not have any revenue coming in, we were giving money back to customers. At one point we had about $150 million a day going out and basically nothing coming in.

You have to have a lot of faith. You have to have a lot of confidence in the purpose of what you do. We knew our product and our service was critical [to] society, our world, our ability to be and connect and communicate. And while we didn’t have any answers, we were finding out new things and learning every day, and it seemed to contradict what you thought you knew the day before. You just had to focus on what it was that you could control.

What I focused on primarily was reaching out to our people and just keeping them informed. Thank God we had a tremendous video network that we’d already installed for our own internal use so people could tune in and see what was happening.

What were the meetings with your senior team like? What was the dynamic?

This is the room. This is the room [where] we spent our time. My office is right down at the end of this hall. At 9 a.m. every day, including weekends, we would be present, in person, occasionally on the phone. We would share with each other what we were seeing, what we were hearing, the queries we were getting and truly make decisions as a team.

There were about 10 or 12 of us. It was more than just trying to hold the company together. It gave our leadership team a safe place to be. We had one hour allocated for it, and we could laugh, we could cry, we could find solace, and we could express our fear to ourselves. It was our safe place.

It was really important to get through that. Then we walked out that door, and we always walked out as one. We knew what we had to do over the course of that day to get to the next day and the next day. It was just truly one day at a time.

We had to exercise the chemistry this team had. We were a close-knit team, and [we had to] lean on each other in ways that we never had to before. It was important. We became a lot closer as a result of that. We bonded through this fire.

The big unlock was when [President] Trump and Capitol Hill agreed to provide support to the airlines in order to keep their people. Because we didn’t know if we were going to have to let all our people go. The whole thought process was very much about protection. Protecting our people, their health, their safety, our planes, our future, our cash, whatever, it was protecting. It was very defensive in every sense of that word. But once we knew that we were going to have Washington’s support for our industry to make sure that we stayed intact, at least on a six-month basis, we could breathe a little bit of a sigh of relief and then start to play a little bit of offensive tactics.

What have you learned about how to manage yourself and bring a team through challenges?

For myself personally, I’ve done a lot of reflection on that. What I’ve concluded is that there are personalities and behaviors in individuals that are drawn to crises. They run to the fire. They run to help. And there are others that run away. In our industry, particularly the airline industry, we’ve had a series of these preparing us for the mother of all crises, which was the pandemic.

It’s in our genes. It’s about wanting to fix, wanting to protect, wanting to serve, wanting to help. That, I think, was a common bond that our team had. And by the way, not everybody made it through the pandemic. We had people leave, we had people retire, we had new people join us. But I think the common trait that we all shared was that desire to lean in.

Is this something you now look for in folks that you surround yourself with?

No question about it. We don’t know what tomorrow brings. All we know is it will be something. And in general, when something’s happened, it’s not good. We know that. So, how do you prepare yourself? How do you not get thrown off when you hear bad news? I’ve long said in this industry, we’re not really great at managing prosperity. We’re really good at adversity. In fact, when things are too calm, I get a little uneasy. I look around to see, what am I missing?

What our world, and certainly our company, was looking for was not someone who had the answers. They were looking for someone they could place their trust in who would lead them through and bring us all through that episode together. There was a vulnerability, there was an honesty, there was a transparency, there was a sense of support that I received from our team, and I gave back to our team. We went through some real human emotion together.

We had people die, family members, colleagues. It brings about every part of who you are. At the beginning of the pandemic, [Delta Chair] Frank Blake shared with me that this crisis would reveal the true character of our company, of our leadership, of myself personally.

He knew what the outcome was going to be. And just that vote of confidence, not knowing what we were going to see but knowing how we were going to approach it and lead through it, gave me all the faith I needed and confidence to get this.

How do you manifest that in the way you’re interacting with other people during a crisis like this?

It’s staying positive when there’s nothing to be positive about, right? I’ve been fortunate to have had a good relationship with Jim Collins. I’ve done a bunch of work with him, and he’s done a bunch of work here at Delta as well. He talks a lot about the Stockdale Paradox. About having this faith that you’re going to get through it that is unrelenting, despite the fact that you understand the harsh, dark realities of what you’re going through.

So you’re honest about what you don’t know, but you have enough confidence in who you are that you’re going to get through. It’s this balance that you keep. It’s that confidence and that drive, that every single day you come back, and you just keep working on it, and you keep working on it, and you’re not going to give up, and you’re going to keep working on it. Eventually, things are going to break.

You just have to stay in the game.

Yeah. Because miracles happen. You just have to stay present. You have to spend time communicating to your people and keeping them safe. You have to spend time with your customers letting them know how you’re thinking about this. As part of getting support from the government, we had to agree, as an industry, that we weren’t going to drop any routes. Now, frequencies changed, but we flew every single route to every single city in the U.S. The international skies were closed, but not in the U.S. because doctors needed to get to the sides of the sick, and loved ones needed to be at the bedsides of those that were dying, and the supply chain of the country needed to continue to operate. Small business through it all was still moving.

I was flying a lot through that period of time. There would only be maybe 5 to 10, 15 people on a plane. There wasn’t a single plane I was on that people didn’t stop and thank me. Because they weren’t traveling because they wanted to travel. They traveled because they had to travel. And they thanked me for keeping our planes and our skies open. That gave me just such a sense of pride that we were able to make that kind of difference in such a dark time.

Paradoxically, though, when you’re in a crisis, it’s easy to see the mission. How have you taken forward that experience to deal with the day-to-day now?

Well, the mission is extremely apparent in that demand for our business is at levels we’ve never seen before. By the way, it’s been that way for almost a year and a half now. You know, once the world, at least in the U.S. and eventually the world, decided that they were done with staying at home, everyone wanted to go someplace, and they didn’t care where they were going. They just were going.

So, we had to stand up this whole business. It was like, “Oh my gosh, how are we going to now get this whole airline that we put to bed largely stood back up in a matter of weeks to be able to accommodate?” This is a company that hadn’t seen revenue in a couple years, so you wanted to grab every dollar you could find, right? So, getting staffing in place, getting the company aligned around getting your planes ready, getting your maintenance support, getting your airports and security and new procedures around travel, and international markets starting to slowly open, that by far has been the most difficult part of this journey.

How do you lead through that kind of whipsaw? How have you been able to maintain day-to-day intensity? You’ve been at this for years now.

Yeah, and we’ve got probably a few more years to go too. When we went through that dark period, I never showed that I ever doubted. Of course, internally you have a lot of doubts. You just don’t share them. But I never externally expressed that doubt that we were going to get there.

When you actually saw, okay, we got through, there was a lot of joy. And again, it was hard, but you worked with your operators. We hired 30,000 people in the last year and a half with training and pilots and supply-chain issues and aircraft. Every part of our operation we had to rebuild and stand back up. And by the way, we did a lot of it differently. We made a lot of changes during the pandemic.

We built new airports when people weren’t traveling, like at LaGuardia or LAX, or what we’re doing at JFK, finishing that out. We built new technologies. We decided to move our company to the cloud through that period of time. We got rid of all the Wi-Fi on our planes. We got new Wi-Fi that works. And all these things that we did were opportunistic, to take advantage of the fact that we knew we were eventually going to need them at some point in time. That also got people excited and charged up. Again, the communications were constant. I mean, it was always very visible, whether it was in large groups, small groups, whether it’s on telecommunication, whether it was on TV.

However we were, we just prided ourselves on keeping the message out in front of people so that they always knew. I was also very accessible. I’m a very easy person to find on email because I only have one [address], I only have one phone number. One of the pieces of advice that I received when I became CEO was that I was too visible and I needed to kind of have a private identity, have a private email, private phone, a fake address or whatnot.

I said, “Thank you very much. I’m not doing that.” Because I want to hear what’s going on. I want to hear every day about how we’re doing and what we can do differently, what we can change. That’s as much with our employees as it is with our customers. I see it all. I’ve got a whole team of people that sit behind me, but I see it all. People are amazed.

That sends a message to your people about engagement, about being present, being of service, being available. I often joke with our operators that I know what’s going on in the operations before they tell me because my phone will tell me everything I need to know on pretty much a minute-by-minute basis. We have all kinds of reporting and all kinds of tools, but it’s common that that all the messages get filtered when they come to the top of an organization. This phone doesn’t. I hear the gory details of whatever’s happened in the businesses. Sometimes it’s not too pretty.

People say, “Well, how do you manage all that? Because that just sounds like a headache.” And I say no, we’re a very hands-on business. It actually enables me to feel confident that I know what’s going on. I’m never having to walk around asking.

You go through a crisis like this, you’re so loyal to these people. How do you know when to promote, when to remove, when to deploy?

There’s about—you can see the number of chairs around here. This is the number of chairs that we have, basically the leaders that report in to me. We did have a number of people leave; we had a number of retirements. Our COO retired six months into it. Our CFO retired nine months into it. Another fellow that was close retired. They kind of looked at what was happening, a couple were attracted to other opportunities, and I wish them well. I didn’t make them feel they let me down. I appreciated all they did for us.

It gave me a chance to reshuffle the deck. I’d say half the chairs in this room are occupied by people who were, certainly they were not in their job or not even in the company pre-pandemic. I say that to people and people are surprised because an airline is highly technical, highly operational, with a lot of years of service to get to this level. We got a new CFO that we hired, Dan Janki, two years ago, and a head of health, Henry Ting from the Mayo Clinic, Alain Bellemare, who came from Bombardier, who’s running our international operations. I just hired a new COO, John Laughter, out of the PepsiCo system.

All these people have come together from different backgrounds. In our business, each of these leaders are really strong leaders, they run big operations respectively, but it was sitting around this table that allowed them all to connect to each other. Because we’re integrated. Unlike a lot of businesses where you have self-standing products or subsidiaries or divisions that are full P&Ls, I only want one P&L. It’s a big P&L, it’s a $50 billion top-line P&L, but it’s just one P&L.

Some CEOs like to build that Jack-Welchian competitive rivalry between folks in the room to breed energy.

I think that’s so dysfunctional, and I think as a result of that, we’re not a political organization. If you come into our organization and you’re political in some way, you’re like oil and water. You just don’t fit—and it’s obvious who those people are. We generally see that on the way in, but in the case we don’t, we can identify it early. We have a system here that works.

We do it differently than other airlines do and other businesses do, but we’re entirely a team sport. That’s why we were in the office every day during the pandemic. That’s why our offices are right across from that tarmac. That’s why we’re sitting in the original headquarters.

So you are looking for high-EQ people who can build and work together under pressure. How do you personally vet for that kind of personality?

Culture is everything at this company. There are a lot of smart people in the world, and you don’t get in the door here unless you’re smart in terms of having an interview or having some level of success along the way. But we screen for culture, we screen for service. And by the way, it’s true whether you’re going to be our CFO or you’re going to be starting as a flight attendant. How do you demonstrate service? How have you demonstrated service in your life? Whether it’s in your past achievements, whether it’s your past companies, whether it’s what you do in your community, it’s who you are. Because you can’t teach culture. You either adapt to the culture and you’re part of it, or you get rejected by it.

This is very much a service business. In our industry, we don’t have competitive advantages that you can just lock away. There’s not a different type of plane we fly versus our competitors. We all pay for fuel at the same price. There’s not a different airport that we go to.

Everything we do in our business has so many common themes to it. At the end of the day, the only thing that’s truly unique about our company is our people and our culture. That’s what our brand consists of.

In order to be part of the leadership team, you have to be someone who’s going to be part of that brand and part of that team and be able to lead your people to it. We talk a lot about servant leadership in our business, and that’s how we think about the philosophy here.

Another change in leadership with CEOs over the past several years is leaders choosing to speak out on important social issues, political issues. You’re no stranger to that. How do you decide when to speak out, when not?

You don’t want to be a politician. We have plenty of politicians. You don’t want to be a social activist. You want to be the very best CEO you can. So, that means that when these issues come up, you have to ask yourself, “Is your comment, your input, relevant?” You have to ask, “Why are you getting engaged?” I’ve learned the hard way that whatever topic, even if you think it’s relevant, you’re still going to get blasted by 50 percent of the people who disagree with you. And by the way, that’s within the company even at some level. Even within your own 100,000 people, we’re a big society ourselves.

But is it relevant? And why is it relevant? Why are you feeling compelled to speak? You can’t make it about yourself. You have to make it about your people. You have to make it about your business. Something that is directly either in conflict to your values or in support of your values.

When you frame it that way, then you feel like there’s a reason why you’re speaking other than just “me too.” The voting rights issue here in Georgia was one where we, Delta, are the largest employer of Black people in the city. Our state was a political hotbed during the 2020 election.

Our people had just gone through a very, very hard time following the pandemic and [the murder of] George Floyd. We’ve tried to build and invest in them, and in equity, letting them know that their voices matter. Then, on the other hand, they see something where they feel like they’re being targeted at some level. [As CEO,] you can’t say, “I don’t have a point of view.” It’s just not genuine. Being the largest company in the city, in the state, if I wasn’t going to speak, no one was going to speak.

Now, it was unpleasant. I didn’t enjoy the experience at all. I’m fortunate to count Governor Kemp as a friend. I support Governor Kemp, but there are things we disagree on, and that’s one we disagreed on. We were able to disagree. There was some blowback, but we kept moving forward because we realized that we needed each other to continue to run forward.

I’ve come to learn that if you speak about what you stand for, why you do what you do, what your purpose in the world is, the values that you share, and you stay vigilant about that, when something comes up that’s in violation, people will say, “Okay, at least I understand that perspective.”

The times you get in trouble are when people say, “That came out of left field,” or “They changed their minds, they did this and then they did that.” That’s when you get into real difficulty, when people are surprised. So I’ve tried to continue to lead from the front on this and let people know who we are.

But it’s hard, and by the way, it’s not getting any easier. We just take that one day at a time. Because we all grew up in business learning you want all your customers to love you, and you don’t want to find yourself on the front page of anything. You’d rather just be going about your own business. It’s been a completely new learning and new world. We’re entering a big election year next year, and I’m guessing it’s going to have its own challenges.

You’re also a technology company that makes massive technology bets. What do you see coming, and what do you think other CEOs should be looking at when they’re placing strategic tech bets over the next decade?

I talk about how our people are our brand, our technology is our lifeblood. It’s what enables our people to do the job they do. That has meant giving our people the tools and the technology to provide better service and support.

It’s beyond that now. Particularly during the pandemic, we really accelerated. It’s now about giving not just your employees but also your customers the tools to manage the experience. Customers tell me, “I love your people, but I love your app even more because I can control it. I can make changes, I can do this, I can plan, I get notified. I feel like I’ve got that Delta red coat right in my hand, right in my palm.”

Digital transformation for me is a journey that we still have quite a ways to go on to continue to get better. AI for me is an area that’s got a lot of potential, but it’s also got a lot of risk if not done well.

We have some early use cases, and I’ve seen some of the displays, and they’re pretty incredible. You watch this big machine learning thing spit out answers to internal stuff here that would take a reservation agent five minutes to hunt and peck through to get a simple answer. You pop that into an AI format and in three seconds the answer is there in a clean eight-word sentence. It’s like, wow, this is magical. But it’s only going to be as good as the information you have.

The challenge for a lot of big companies is: You don’t want to start to implement a whole lot of AI on your existing data. Because we know our data isn’t necessarily as clean or consistent or whatnot. And you never want to have your people feel like they’re just turning into a chatbot. So you have to think about how you apply the AI to add creativity, to add value to the experience.

The big opportunities for me at Delta with AI are going to be ones about optimization. We have 1,000 planes; we fly 5,000 times a day. We fly in all kinds of variable conditions, all around the world. We don’t operate 24/7. We operate 48 hours a day because our time channels and international operations are always 48 hours to every day that we’re operating.

In the midst of that, you’ve got fuel, you’ve got 15,000 pilots, 30,000 flight attendants. You’ve got mechanics, operational updates, things happening at all times. Just keeping that whole thing wired together so that you’re telling this plane to go here or having this crew go there, we’re required to have a lot of reserve, a lot of excess in the system.

A flight attendant in Shanghai calls in sick, what are you going to do? You’ve got 300 people who have to spend the night in Shanghai? No, we have reserves in Shanghai to handle it. The big idea for AI for us is how do you take that Rubik’s Cube of all this operational variability to the nth degree and use the machine science to deliver better results, better answers, better predictive tools that you can then apply to your decision-making.

But you can never get to the point where you feel like the machines are making decisions and replacing human judgment in our business because of safety. It’s a big issue. It’s not about jobs. It’s about always making certain that safety is the number-one thing. It’s far more important than efficiency. You’ll eventually find a solution where AI will be flying the airplanes, and you don’t need pilots in the cockpit. Well, that’s not going to be on Delta. There will always be two pilots on a Delta plane. That’s how it’ll always be. That mix of human ownership and visibility and review and value—managing the technology will be the key.

But I’d say 10 years from now, massive opportunity. I’m very much of the view that we’re going slow to go fast. Because this is not something you just jump right into. I know there’s a lot of FOMO going on. No one wants to miss the opportunity. The technology companies are feeding that a little bit. But we’re learning. We’re going to get smart, and when we go, we’ll go big. It’s just a massive opportunity because we’re a massive data company.

We’re living in an age of so much change, so fast. How do you help process that change so it doesn’t rip up the culture while you’re trying to deploy the technology?

The key for CEOs, at least in my view, is you have to stay ahead. It doesn’t mean that you’ll necessarily be understanding what the technology of the future is going to be, but you have to stay far enough ahead of your business as to where you want to take your business. Because you control where you’re going with the company, not the technology. That’s the unique purview of the CEO—to be someone who can be five years ahead of the company.

No one else in the company, including the board by the way, really has the responsibility or the capability to be out there starting to place those bold markers. I get a lot of help in thinking about it. But you’ve got to be the person out there staying ahead of the fray.

I’m a big believer that you can lead the change, or it is going to change you. I prefer to think I’m going to change it by staying ahead of the game and directing where we’re going. You have course corrections every day, but you just keep out there and you’re very vigilant about that. And people will follow. People will follow.