The swelling ranks of contingent workers—a category comprising a wide range of non-salaried, freelance specialists and independent contract workers—are a boon to the bottom line. For a lot less money than hiring someone on a full-time basis, companies can acquire top-notch talent to quickly fill skill-set voids on an as-needed basis, without having to make contributions to Social Security, unemployment insurance and workers compensation or manage tax withholding.

The swelling ranks of contingent workers—a category comprising a wide range of non-salaried, freelance specialists and independent contract workers—are a boon to the bottom line. For a lot less money than hiring someone on a full-time basis, companies can acquire top-notch talent to quickly fill skill-set voids on an as-needed basis, without having to make contributions to Social Security, unemployment insurance and workers compensation or manage tax withholding.

They also save on healthcare, sick leave, overtime and paid vacation time—not to mention the other benefits that highly skilled, full-time workers expect these days, such as dental plans, life insurance, disability insurance and gym memberships. These various expenses add up. According to MIT Sloan School of Management, the total cost of an employee can equate to as much as 1.4 times the person’s base salary. The financial benefits of contingent workers and the growing interest of many people in such work arrangements have combined to create today’s “gig economy.”

Like neighborhood rock bands playing a wedding one week and a bar mitzvah the next, contingent workers take on short-term gigs, offering their unique talents to multiple employers. They choose how much they want to work and for whom, enhancing their work-life balance.

That’s the upside. Like everything else that seems too good to be true, there are sobering downsides to the gig economy. Contingent workers may not align with the hiring organization’s culture, their independent natures rubbing up against a business with a collaborative workforce or a hierarchical command-and-control structure. They also tend to make older, full-time workers uneasy. Plus, they impose major employment and labor law compliance risks. Woe to the company that misclassifies a full-time employee as a contingent worker. (See “Is Your Contractor Really an Employee?”)

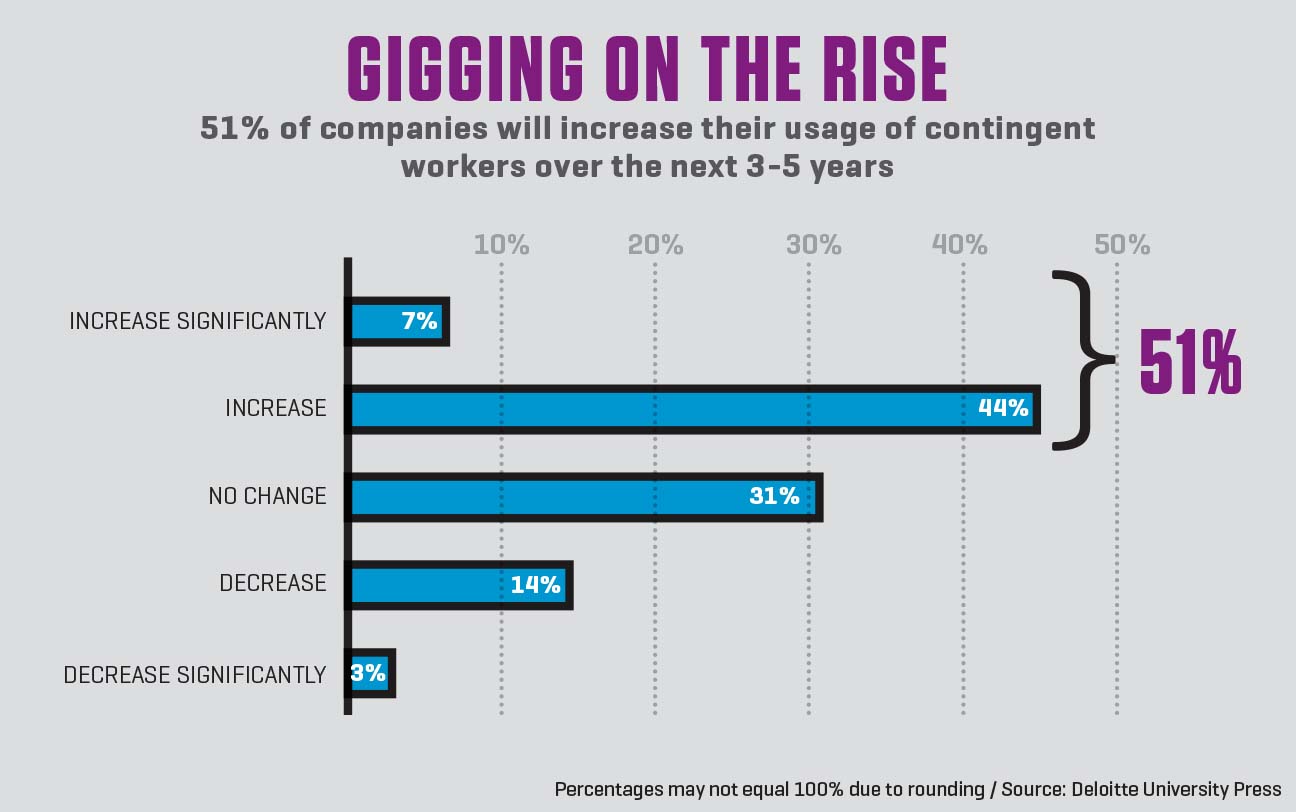

Still, the sheer growth in the size of the contingent workforce appears to affirm that the benefits are well worth the risks. According to a 2015 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), 40.4 percent of the U.S. workforce is made up of contingent workers. As defined by the GAO, these include independent contractors who provide a service or product, part-time workers, self-employed workers, contract company workers, agency temps and on-call workers who cycle in and out of companies on an as-needed basis.

One of the biggest bumps in the category is in people working as independent contractors. These individuals include skilled specialists, such as computer programmers and software application designers and developers, as well as workers with creative writing, graphic design and similar talents, among others. In 2005, such workers made up 11.9 percent of the labor force. Ten years later, they made up 16.2 percent, a 36 percent leap.

GIG GENERATIONS

GIG GENERATIONS

Entrepreneurial and independent-minded Millennials, who prefer to provide their talents on a short-term basis to multiple takers, account for a significant number of such workers. These members of the workforce shun spending their careers with one, two or three employers like their parents and grandparents. “Millennials tend to have high-level ideals they want to pursue, working to live and not living to work,” explains Sean Monahan, a partner with consulting firm A.T. Kearney’s operation and performance transformation practice.

Even when Millennials take full-time positions, they don’t last long. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median job tenure for workers aged 20 to 24 is shorter than 16 months. For those aged 25 to 34, the tenure is three years. Everyone else works longer than 5.5 years. “Millennials often look for jobs where they can pick up some expertise and knowledge and then move on to the next opportunity to continue learning,” Monahan says.

Younger workers aren’t alone in this sentiment. However, more seasoned gig economy participation is not always by choice; many Baby Boomers not yet ready to retire and other experienced workers were casualties of the Great Recession.

“A lot of people, such as software engineers, were laid off and started working part-time,” says Josh Bersin, principal at HR consultancy Bersin by Deloitte. Some grew to prefer that arrangement; others were simply unable to find comparable salaried work. Retirees with singular expertise that can only be developed over long careers are also being lured back into the workforce to offer short-term service.

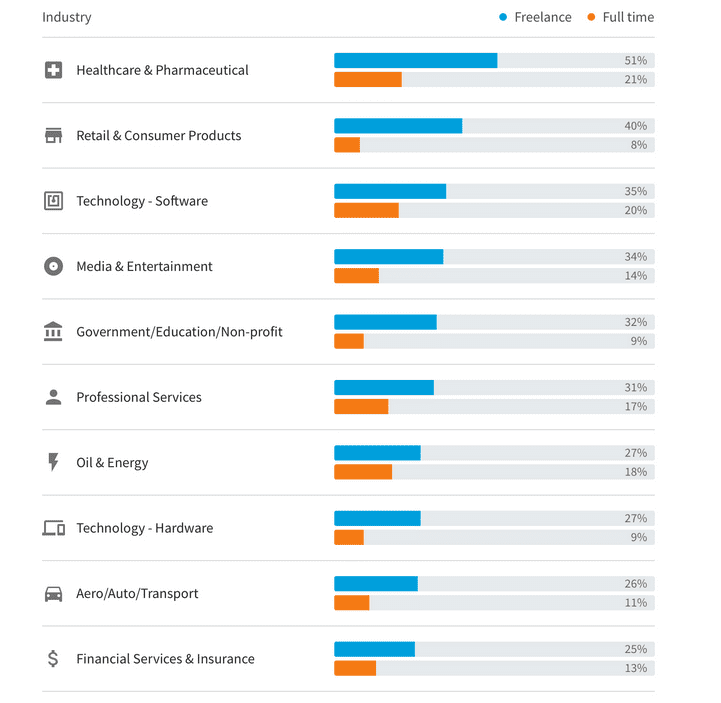

A SKILL SET SOLUTION

For companies, contingent workers represent a potential solution to today’s high turnover rates and dearth of skilled workers. Resourceful businesses are countering these issues with “total workforce solutions,” a term referencing the different types of salaried and non-salaried workers needed to realize business strategy. Among them is Hallmark Cards. “We have the need for talent in a variety of skill sets, such as technology, creative and industrial,” says Fred Wise, the greeting card manufacturer’s HR director. “To fulfill these needs beyond our salaried personnel, we will leverage alumni, former Hallmarkers, in addition to freelance, independent talent for variable or less predictable work.”

For companies, contingent workers represent a potential solution to today’s high turnover rates and dearth of skilled workers. Resourceful businesses are countering these issues with “total workforce solutions,” a term referencing the different types of salaried and non-salaried workers needed to realize business strategy. Among them is Hallmark Cards. “We have the need for talent in a variety of skill sets, such as technology, creative and industrial,” says Fred Wise, the greeting card manufacturer’s HR director. “To fulfill these needs beyond our salaried personnel, we will leverage alumni, former Hallmarkers, in addition to freelance, independent talent for variable or less predictable work.”

Cisco Systems also turns to contingent workers to address talent gaps. “When we can’t find someone with a particular skill set through traditional recruitment, we’ll reach out to contingent workers,” says Jeanne Beliveau-Dunn, the technology giant’s vice president and general manager. “We’ll pay a lot of money to get the person’s expertise and like it when they want to stay on in a more permanent capacity. As part of the arrangement, we also expect them to A cottage industry of open sourcing talent platforms has cropped up to introduce employers to a broad spectrum of contingent workers.

Such intermediaries as Upwork, OnForce, WorkMarket, Shiftgig and FieldNation are to contingent workers and employers what yentas are to the marriage business. “The accessibility of talent has changed enormously,” says Christopher Dwyer, research director at Ardent Partners, a research and advisory firm. “Companies have instant, on-demand access to this pool of incredibly talented freelancers and other independent professionals. You contact them directly when you need them and set the parameters of what you want and are willing to pay.”

“It’s the uber-ization of the workforce,” agrees Neil Shastri, leader of HR consulting firm AON Hewitt’s global insights and innovation practice. “It’s so easy nowadays to recruit high-skilled freelancers across diverse professional disciplines when you need them.” “Companies want specialists, people with particular skills, as opposed to the well-rounded generalists that business schools historically graduated,” adds Mike Mulder, senior vice president, program management, at Bartech Group, a contingent workforce and staffing solutions provider. “When they can’t find these skill sets in a full-time context, they have little choice other than to source them on a contingent basis.”

Both parties benefit, with skilled freelancers getting to choose when to provide their talents—and for whom—and employers securing talent at a lower overall cost.

NAVIGATING THE GIG ECONOMY

Leveraging contingent workers, however, requires some finesse. Full-time employees often resent the presence of their independent-contractor peers, believing they’re taking work away from other full-timers or given greater flexibility or higher pay rates. “For older, longtime employees, it’s intimidating to know that the way the work has always been done is changing,” Dwyer says. “From a cultural perspective, they’re not sure how to collaborate with these people.”

Centralization of employment is one way that companies can address such issues. Many companies secure contingent workers through both their HR and procurement functions, with each group pursuing its own agenda. Recruitment is often left to different hiring managers across the company. Either finance or legal departments are tasked to contract contingent workers. There’s no transparency in this siloed approach, and thus no visibility into overall workforce management.

More sophisticated companies, however, are creating governance committees consisting of individuals from HR, procurement, finance, legal and IT to work with managed services providers like Bartech in creating a comprehensive workforce policy. “We function as a liaison between this ownership team and the staffing providers, handling the contractual issues to ensure compliance and worker security,” Mulder says.

Hallmark pursues this route, utilizing a Managed Services Provider (Guidant) as its contingent talent central request and control function. “They work with managers who have short-term, variable or on-demand work assignments to identify the right type of contingent talent to meet these needs,” says Wise. “They’re also responsible for ensuring appropriate employment classification of contingent workers.” Cisco takes a different tack, managing its own workforce needs and compliance obligations in-house, as opposed to outsourcing it. “We have a stream of authorized staffing companies we work with, which is determined by our HR leader,” says Beliveau-Dunn. “We also directly source contingent talent through online platforms like Upwork.”

In either case—insourcing or outsourcing—companies that effectively manage the pros and cons of contingent workers will outpace their competitors, since people are the most important business assets of all. “In a way, the use of contingent workers is a return to how people worked prior to the Industrial Age, when everyone had a particular skill learned under an apprenticeship,” says Pete Sanborn, global practice leader of AON Hewitt’s Talent and Organization practice. “For efficiency reasons, mass scale employment replaced this concept.”

Now, thanks to technology and the desire for more meaningful work experiences, the efficiencies of the old artisan economy compare quite well with traditional employment.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.