Until recently, global management consulting firm Deloitte had a performance management system similar to that of most other big firms. Objectives were set for each of the 70,000-plus employees at the beginning of the year. Evaluations were done as projects were completed. Both were then factored into a single year-end rating, which the employees received as feedback in their end-of-year annual performance reviews.

Until recently, global management consulting firm Deloitte had a performance management system similar to that of most other big firms. Objectives were set for each of the 70,000-plus employees at the beginning of the year. Evaluations were done as projects were completed. Both were then factored into a single year-end rating, which the employees received as feedback in their end-of-year annual performance reviews.

Then, in 2012, Deloitte decided to start digging deeper into the numbers and found something shocking: Completing annual review forms, holding meetings and creating employee ratings consumed a whopping 2 million man hours per year—most of it spent with managers behind closed doors discussing past performance rather than top performers’ future prospects.

“We wanted to get away from a system that was about an arbitrary assignment of a numerical rating to one that was about getting people focused on developmental conversations,” says Mike Preston, Deloitte’s chief talent officer. That led the firm on a course to completely change the way it collects data on employee satisfaction and performance, how it recognizes that performance and how it drives even better performance. Although the longitudinal data is not yet in to prove a correlation with retention, says Preston, “I do know that if it’s increasing engagement, it will reduce turnover.”

Deloitte is one of a growing number of companies, including Accenture, Microsoft, Medtronic and Adobe, ditching the traditional “rank and yank” method of talent evaluation, which falls short not only in evaluating talent but also saps morale and leads to frustration and voluntary attrition. With the talent war raging once again, employee retention and turnover are the top focuses for HR professionals, who, in a recent survey by the Society of Human Resource Management, report that these are the biggest challenges their companies face today.

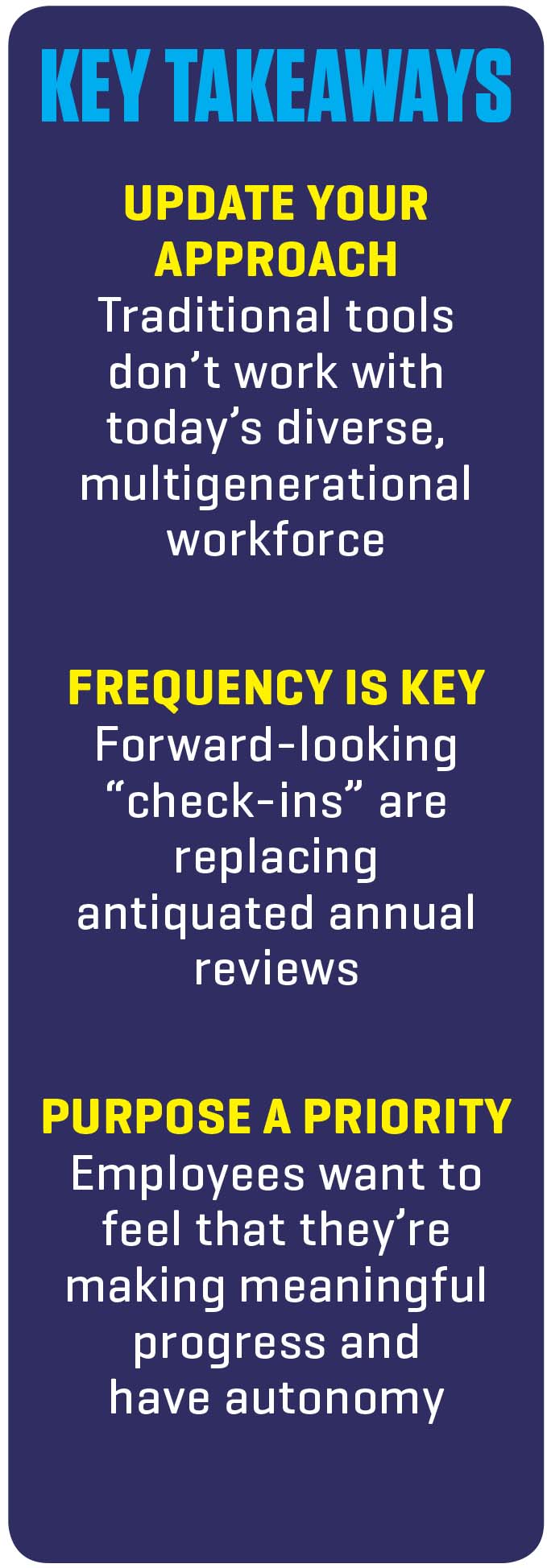

CEOs are increasingly finding that the old methods of engagement don’t work for today’s diverse workforce, whose members seek not only competitive pay, but also flexibility, recognition, mentorship, a sense of purpose and a clear path to their next job. When they don’t get those things, they tend to walk. “When we have someone leave Deloitte, they don’t leave for money,” says Cathy Engelbert, CEO of Deloitte. “They leave because maybe they didn’t feel they were valued.”

Engelbert sees it as her role to set the tone and engage her own team of leaders, which then cascades through the workforce. “As CEO, I see an important role for me in driving culture, especially when managing a diverse and multigenerational workforce.” A look at how top employers are experimenting with new tools for engaging their best employees reveals the following best practices.

1. KILL THE ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REVIEW

The time-honored tradition of getting together with direct reports in a closed-door session to reveal strengths, weaknesses and the year’s compensation numbers is a failure, says Preston. For starters, “you’re often reviewing something that happened nine months ago,” he says. A better bet? Change the focus from remediating past behavior to the future career of that employee and what will energize him or her to want to do better.

Millennials, in particular, don’t want to be told where they stand once a year. “They’ve grown up in a culture of transparency, in a world where you can get online and see what people think about everything—good, bad or indifferent,” says Erika Anderson, founder of coaching firm Proteus International and author of Leading so People Will Follow and Growing Great Employees. They want the same transparency at work, she says.

“The Millennial is used to rich, robust information—all the time,” agrees Daniel Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. “Then, we bring her into a large organization and say, ‘I know you’re used to rich, robust, meaningful feedback every waking hour. But here, we give you feedback once a year in an awkward kabuki-style theater in an office.’ How do you think that will work for her?”

Adobe realized its approach wasn’t working back in 2011 and was the first to implement a completely different system of communication between managers and employees: the CheckIn. The new system required managers to convey what was expected from their employees clearly, to give and receive feedback and to provide opportunities for personal and professional development. The form and the frequency of check-ins were left to the discretion of managers, although conversations are required once per quarter at a minimum, with many doing it monthly, weekly or even daily. Because managers must also be open to feedback from employees, Adobe established organization-wide leadership workshops where managers were trained on how to deliver constructive feedback and receive feedback about their own performance as team leaders.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.