Dean Krehmeyer, an executive director of the Business Roundtable, says, “The myopic focus on short-term results not only undermines longer-term value, but is legally inconsistent with leading governance principles.”

A number of CEOs, such as Whole Foods’ John Mackey, the co-author of Conscious Capitalism, have been asserting that CEOs need to climb out of the self-created hole they have dug for themselves. And this doesn’t even touch the question of who the shareholders actually are.

Short-termers have taken over the stock market. In the 1950s, the average holding period for an equity traded on the New York Stock Exchange was about seven years. Now it’s six months. Similar trends can be seen in other markets around the world.

In a more recent development, high-frequency traders whose holding periods can sometimes be measured in milliseconds now account for as much as 70 percent of daily volume on the NYSE. Can such a “shareholder” seriously have the interests of the company whose shares he is holding in mind?”

What is particularly galling,” wrote Charles Wohlstetter, chairman and co-founder of Contel, an integrated telecommunications company as early as the March 1990 issue of Chief Executive, “is the write-off of individual investors by the technocrats and institutional traders who dominate trading today.”

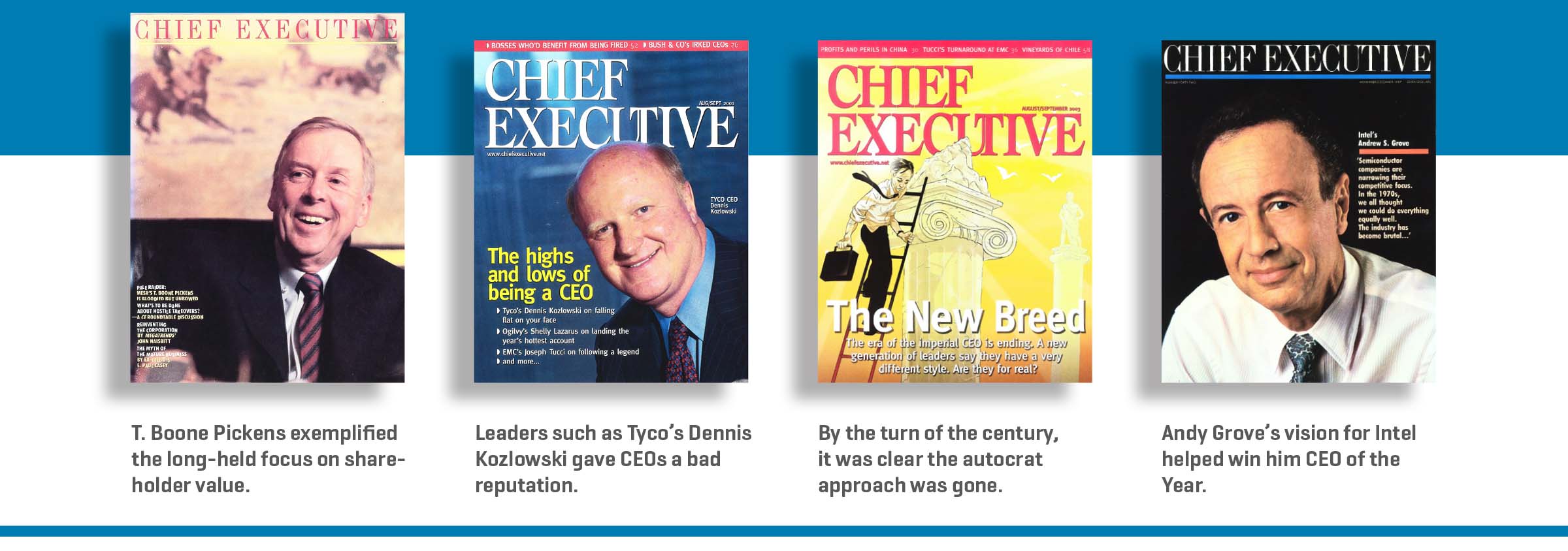

Prior to the 1970s, managers and directors viewed themselves not as shareholders’ servants, but as trustees for great institutions that should serve not only shareholders, but other corporate stakeholders as well, including customers, creditors, employees and the community. Equity investors were treated as an important corporate constituency, but not the only constituency that mattered. Nor was share price assumed to be the best proxy for corporate performance. Activist investors will continue to push for their narrower interpretation of value. The times will require a senior CEO statesman to boldly advance what appears to be a new way of thinking about value creation and the appropriate role of the corporation.

GLOBALIZATION AND TECHNOLOGY CHANGE THE DYNAMIC

Forty years ago, we saw how most CEOs were autocrats. They micromanaged to make sure everyone was doing what they were supposed to be doing. Since then, two powerful forces have greatly altered this: globalization of markets and technology.

For example, 20 years ago, a company such as Sealed Air, a packaging company at the lower end of the Fortune 500, was typical of most U.S. firms. No more than 35 percent of its sales derived from markets outside the U.S. Today, that figure represents almost two-thirds of its total.

In the 1980s, nearly every manufacturer complained about Japan Inc. and how it was eviscerating American manufacturing. Today, no one talks about Japan Inc. And even today’s discussions about trade relations with China have been tempered by how globalization and technology have changed the dynamic.

Both forces have greatly increased the complexity and the speed of change rendering autocrats as worse than useless; they can be ruinous. What is required to create a great product or service is well beyond one leader. The world is moving so fast now, and technology is changing every industry.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.