Know it or not, like it or not, no single business thinker of the past 50 years has had as much impact on the day-to-day way you run your business than Clayton Christensen. With his seminal 1997 work The Innovator’s Dilemma, he diagnosed one of the most intractable problems in all of capitalism: Why do great companies die? What actually happens to them?

The answer, as almost everyone reading this probably knows, was what he termed “disruptive innovation,” the theory that fleeter companies targeting the low-end of markets from software to steel find cheaper, more effective ways of getting customers what they want—and derail their ossified, high-end competitors in the process.

This key insight spawned an entirely new way of looking at competition and served as the intellectual underpinning—sometimes misguided—of the “disruption revolution” fueling Silicon Valley. It would be enough for anyone to dine out on for an entire career, but Christensen continued to develop and refine his thinking over the next 20 years. With his latest work, The Prosperity Paradox, co-authored by Efosa Ojomo and Karen Dillon, he’s turned his study of innovation on the largest, most intractable problem in the world: creating prosperity.

His solution is simple, profound and right in front of your face: See big problems as big opportunities. Look for the intersection of non-consumption and what he calls “jobs that must be done.” Then create products—and processes—that serve those needs. By doing so, you’ll harness what he terms “market-creating innovation”—by far the most profitable, disruptive force in business (think electric light, iPhones and the Model T). Bonus: You’ll help a lot of people, too.

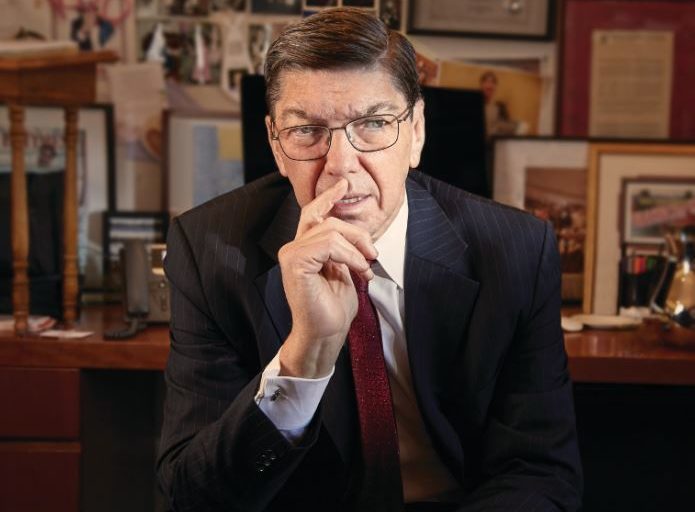

Christensen recently welcomed us to his cozy office at Harvard Business School, where he’s taught since 1992. It’s chockablock with books and mementos of a career enmeshed in the study of how business actually gets done. Our favorite: a chime made of rebar, commemorating his deep-dive into the inner workings of the steel industry. “I’ve learned a lot about the world through rebar,” he chuckles.

Slowed by cancer and a stroke (which forced him to re-learn English from scratch), Christensen is buoyed by his deep Mormon faith and an unending curiosity about other people. He starts the interview by asking us about our backgrounds. With anyone else, it’d seem like studied salesmanship. But not with Christensen. He listens, his eyes focused and glistening with feeling. He’s humbled. He’s happy. He’s learning something new. Ten minutes later, we finally get around to asking him our first question. What follows are excerpts from the conversation with Christensen and his co-author Efosa Ojomo, edited for length and clarity:

Clay Christensen: Well, I’m ashamed to say I can’t remember where I was sitting when we had the insight. But we realized this concept of you can push solutions to the problem of what’s going on in the emerging world or you can make it happen by jumping ahead. Capitalism jumps ahead of the problem. It comes around the problem and just pulls it in, and it fills a [need].

Efosa Ojomo: [Clay’s] theories were leading us. We didn’t necessarily want to write a book about business or capitalism. We just looked at the theories and said, “What does the theory have to say?” There is a way the world works and there’s a way I want the world to work. And those are two very different things.

The first time I went back to Nigeria—which is where I’m from—after being in America for eight years, I visited a village, it was very poor, didn’t have access to water. Women at the banks of a river washing clothes walked miles to get there and would have to walk miles back to the village. Instantly I said, “The solution is a well.” So I pushed a well into the community. I raised money from France, we built a well, we were happy and excited. Then I came back to America. A few months later the well broke down. I couldn’t do anything about it. What I learned is, that’s how I wanted the world to work. You see a problem, you help people, you fix it. But there wasn’t any mechanism, there wasn’t any ownership or organization around the well, and so it just stayed broken.

Christensen: One of the theories that we teach here is the theory of interdependence and modularity. You can’t solve part of the problem if you’re not prepared to answer the whole problem. So Dell, for example, is on the end of modularity and to play in that game you just had to have one of each of the components in a personal computer and Dell could go into his dorm room and assemble and then he just made it available to anybody.

He had the U.S. Postal Service, and he could put his arms around the whole problem, and that’s actually very important. If you just do part of the theory, you can’t solve the problem, you have to be interdependent. Thank goodness we have this theory of interdependence and modularity. You’ve got to put your arms around that whole problem.

I was on the board of Tata Consultancy Services and they spent a lot of money to help a lot of people. They had built a school and paid people to support the school. But at the end of the process the graduates didn’t have a job….

I realized that the whole world wants to put their money to solve the problem in the emerging world, but it’s an interdependent problem, and democracy, for all of its virtue, couldn’t put arms around the problem. One day, we were here trying to solve the issue in this conference room, and [we hit on] the idea that the world is trying to push solutions, and instead, what we need is to pull solutions. It’s a very important idea.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.