It’s been a tough year for FedEx and for its founder and CEO, Fred Smith. Battered by a softening global economy, rising trade tensions, an ongoing frenemy fight with Amazon and grumpy investors looking for outsized earnings growth, the company has seen shares fall 25 percent in the past year.

It’s been a tough year for FedEx and for its founder and CEO, Fred Smith. Battered by a softening global economy, rising trade tensions, an ongoing frenemy fight with Amazon and grumpy investors looking for outsized earnings growth, the company has seen shares fall 25 percent in the past year.

Hardly a cake walk, but Smith, of course, has seen worse. Since founding the company in 1971, he’s weathered an endless storm of transformations, each one potentially existential. Oil shocks. Recessions. Wars. 9/11. E-mail.

Through it all FedEx has survived, thrived and grown to a centrality in the global economy perhaps unmatched by any other company. Visiting the night shift at the Memphis hub of FedEx Express (as we did during Chief Executive’s recent Supply Chain and Logistics Summit, see page 64) is to witness one of the most astounding feats of daily human ingenuity: 150 planes and 7,000 employees across 900 acres sorting 1.3 million packages. Every day.

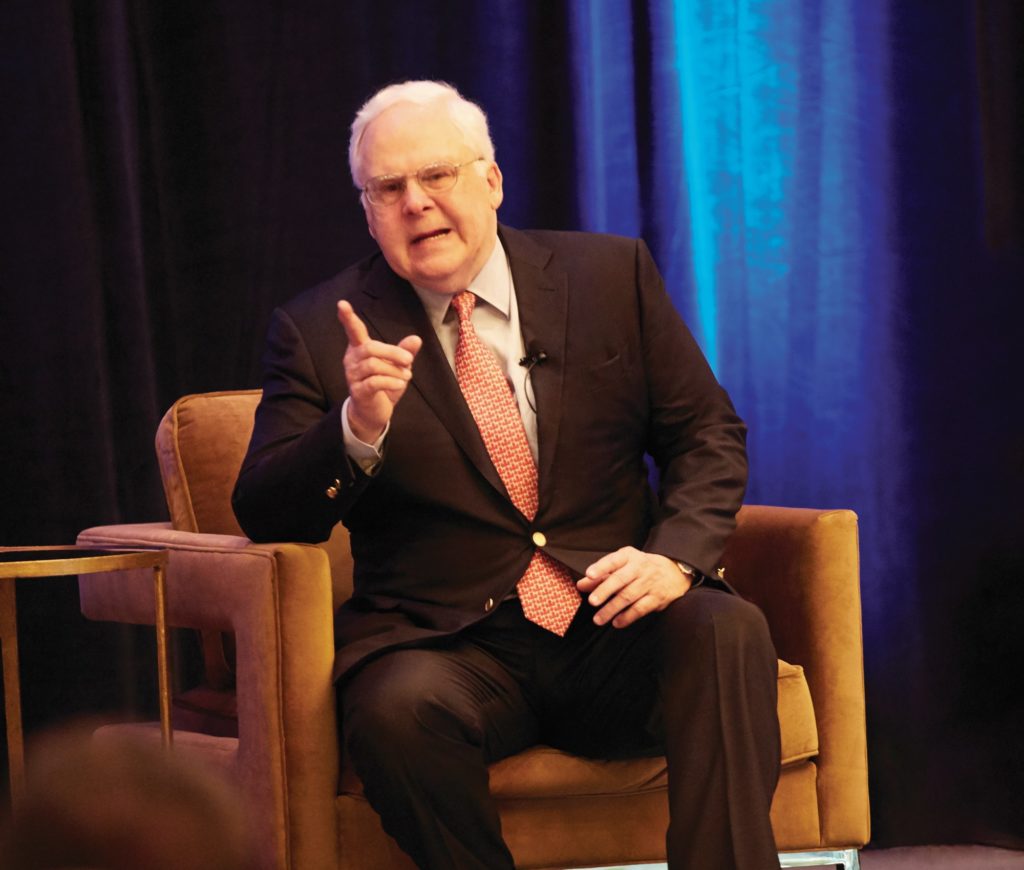

A day after FedEx’s most recent earnings call, in which the company was repeatedly questioned about its spending on new planes and new systems, as well as the headwinds of the economy, Chief Executive talked with Smith onstage at the historic Peabody Hotel in downtown Memphis. The conversation ranged from Wall Street and free trade to his outlook for China and how he sees the future—at FedEx and beyond. What follows is a transcript of that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

First, let me give you a little context about FedEx. FedEx will end up this fiscal year just shy of $70 billion of revenue. Now, we don’t have any cost of goods sold. So, that $70 billion is all EVA, economic value added.

We went into the year thinking we were gonna grow about $6 billion, and we actually grew about $4.5 billion. So even though we didn’t hit our goal, we’re still going to have earnings year-over-year that are probably flat or slightly up… We’re still gonna have, you know, a reasonably good year, is the point that I’m saying to you.

It’s not like FedEx is facing existential challenges. We’re just not making as much money as we had planned and hoped. On June 1 last year, we thought that the year was gonna be strong enough that we could make some very important changes and investments in our business. So we opened up two enormous ground hubs, in Allentown, Pennsylvania, and Middletown, Connecticut. Huge things, 300 acres.

Second, because of the e-commerce revolution, which is a part of our business but certainly not the main part of the business, people want items delivered six and now even seven days a week. So, we went to a six-day operation. So that means we’ve put a bow wave of capacity and expense out there.

And then third, one of the big things about e-commerce nobody talks much about is the tremendous explosion in oversized packages. These aren’t little bitty packages. They’re refrigerators, furniture and stuff like that. So we’ve put a significant new network of oversized annexes in our ground system.

So, then the international revenues did not materialize because of the Brexit situation in Europe and the trade dispute with China, none of which was predictable when we went into the business plan. So, I just wanted to give you that context that we made these expansions to the business, we’re glad we did, and now we’re working hard to make sure that we put the revenues in the systems that justify the expansion.

That’s at the heart of one of the most serious problems with the U.S. economy. Wall Street has this army of analysts trying to figure out our business better than we can figure it out and, more importantly, better than the entire mosaic of the global economy can figure it out. We do 14.5 million shipments a day worldwide with half a million people, 700 planes, 180,000 vehicles, 5,000 facilities. You can’t run a business like FedEx quarter-for-quarter.

Yesterday, we got hammered on an analyst call because we’re not making as much money as we planned, but we just put our goals out there and run the business. We’re making investments for 25 and 30 years, not for the next quarter, but it is very tough on a company run by a CEO who has [only] been in place for four or five years. They feel such pressure to deliver these short-term results, which is a real problem in terms of the growth in the country because it makes management and those CEOs risk-averse and afraid.

The stock market is no longer smart people running pools of capital and investing. It’s mostly run by algorithms. And you’re not talking about little small perturbations. You miss the quarter, and wham, the stock goes down 25 percent. It’s very unstable.

Add the private equity phenomenon on top of that, and that’s why you’ve seen the number of publicly held companies decline by half over the last 25 years. And it will continue to decline because nobody can operate in that type of short-term focus when running a long-term business, particularly when it gets to any scale.

The biggest thing that’s happened is the rise of China. In 1979, Deng Xiaoping figured out what they were doing wasn’t working, and he began to open up China’s economy. With this enormous amount of productive labor available, they became the manufacturing centerpiece of the world, and almost all supply chains were either in the middle of the growth of China or they were peripherally affected by the growth in China.

By the time of the meltdown in the Western financial markets in 2008… other countries started criticizing China. They take people’s intellectual property. They engage in cyber-espionage. They force JVs inside the company. They’re mercantilists. They put lots of tariffs on our products. They use non-tariff barriers. When the tariff fight started, they, as an example, held up hundreds and hundreds of Ford cars coming into China at a port by making some outrageous claim that the catalytic converters or something weren’t up to standard. The net result was the value of those cars went to zero.

They’ve done all of those things, and at the same time, they’ve militarized the South China Sea. They started their so-called Belt and Road Initiative. And, probably most problematic, they have their Made in China 2025 initiative, which identifies a number of industries where they say quite openly, “The state will be involved in these sectors, and we will be the leaders in these sectors by 2025.” China has overstepped, and that has created an enormous economic problem.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.