Given the near-permanent gridlock on Capitol Hill, it’s not that surprising that Americans’ satisfaction with the federal government would be at an all-time low. But confidence in corporate America is now equally depressed, with trust having been steadily eroded by the high-profile corporate scandals and Wall Street crises of the past decade. Big business is viewed as colluding with big government at the expense of the average U.S. citizen. And, owed in part to continued unemployment and a still-limping economy, Main Street sees business as the problem rather than the solution. This gives rise to fear and resentment that undermines the American capitalist system.

Right now, we don’t need any more factors dragging down the U.S. economy. While things are improving from the 2008-09 meltdown, we still face significant challenges: trade deficits, the federal deficit and staggering unemployment. We still have roughly 12.5 million people out of work. Although housing and a few other areas of the economy have begun to improve, in September, credit ratings agency Egan Jones announced another downgrade of the U.S.’s credit rating—this time from AA to AA-. These downgrades are psychologically draining, and they work to reduce the luster and the perceived economic power of the U.S. in the world’s eyes. When we don’t deal with the deficit, we run the risk of more rating declines, which has psychological and financial implications across the globe and will also, at some point when the economy recovers, have an impact on interest rates. This will affect payment of the interest on the debt of the U.S., which will, in turn, further impact the deficit again. It’s a vicious cycle.

For years now, big business has been focused on Washington, but that energy is misplaced. Over the last year we’ve watched political pundits, economists and other talking heads slug it out over which U.S. presidential candidate’s policies would do the most to create jobs, stimulate growth and put American business back on top. It’s the wrong question. Government bureaucrats cannot solve this problem. Partisan gridlock and inertia have paralyzed Congress to a debilitating degree. And even if ideologues from both parties were to do the right thing and come together on Capitol Hill to work toward a solution, it is highly doubtful they would be able to solve the fundamental economic problems.

To solve the nation’s economic woes, we need to drill down to the state and local level, and look to the heart of this country’s economic engine: small and mid-size businesses. A grass-roots effort is needed in each state, with business leaders at the state and local level getting together amongst themselves and, working with state governors, figuring out how they can most efficiently boost economic output and get people working again.

It can be done. The following is a six-step plan that I believe will get us moving in the right direction.

When I talk to executives they can’t even name the secretary of commerce. The job needs to be redefined with a clear purpose, clear responsibilities and clear accountability. The national secretary of commerce should have a detailed agenda to improve U.S. exports that can then be communicated to business leaders, who can make it actionable. Further, each state should have a secretary of commerce or the equivalent, whose full-time job is to do analysis, shepherd businesses to create jobs, coordinate with the governor and labor unions, and liaise with the U.S. secretary of commerce. The job needs teeth.

The only way progress can be made in this area is through coordinated, strategic effort.

Washington does need to get serious about the budget, but while politicians are busy doing so, the business communities and those that lead them should be creating real jobs at the state level. We need to work on growing a trade surplus by focusing on exports. We have a tremendous amount of innovation in America and these exports build a tax base, which will then create more economy in trade across the globe. This initiative to stimulate the economy must begin in each and every state. It’s already happening in places like Maryland, where the governor is leading the effort and bringing business and union people together. Jointly, they are examining the strength in the state, what needs to be exported, what needs to be done. Creating a plan for each state will require analytical skills and customized solutions. Business leaders and their respective state governors need to look at their state’s exports to see which have grown, which have declined and why. Together, they must take the initiative. Consulting firms very likely would provide pro bono help to determine what segments of the economy are exportable from each state to other countries and review what has gone up and gone down.

Small and mid-size businesses are often not equipped to understand and manage exports. They need help from larger companies and the governors in each state who can take the initiative, and get these people to focus on key countries, key segments and foreign direct investment. The states can then provide necessary incentives. If 10-15 states do that, they will have created an export engine that is innovation- and productivity-based.

Job training can be done by the private sector, which can determine what is relevant based on today’s market needs. At the same time, we need to figure out where we have deficiencies of skills and create a coalition of state and regional government and business leaders to provide it. We need programs where business and government work together to identify those deficiencies, devise training programs and create both physical and virtual training programs to address them.

Once businesses in each state have the facts, they need to create a simple agenda that identifies industries, market segments and countries to target for export and what must be done to execute that program. The agenda should show where productivity must be boosted, and which specific regulations are blocking the way to becoming an export engine.

The U.S. has the most innovative minds in the world, but that doesn’t mean we don’t also need to allow immigration. America was built through the hard work of immigrants who moved to the U.S. for the job opportunities it provided. This can still be the case. If immigrants are tapped as a potential source of talent, rather than viewed as a destructive force taking jobs from American citizens, the U.S. would regain and rebuild a more diverse talent pool. These workers have the potential to be at the center of economic growth. Individual states must dig through their import/export data to determine where they are missing opportunities, where they are importing products that they could effectively produce themselves, and further, what goods they have the potential to produce for export. They must then identify what specific skills they need to put this plan into effect, and then put that list together to work with Washington. The work force of new immigrants can be among those trained to man the front lines of this new, thriving economic model.

The U.S. currently lacks coherent policies and programs to manage and control immigration. Further, it needs to support the value-added economic policies of effectively controlled immigration into the areas of the country where new workers are needed most. Other countries, such as Australia, Canada and the U.K., have successfully implemented a two-step immigration system, which first imports temporary workers and then aids them in qualifying for permanent residency.

These steps can help the U.S. begin to grow its exports again, which it must do. In 2011, the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services increased to $558 billion from $500 billion in 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Oil and refined petroleum products account for much of that, but the U.S. trade deficit in non-oil goods—which focuses on things like automobiles, auto parts, electronics and manufactured goods—also increased to $399.7 billion in 2011 from $369.7 billion the year before. The majority of this trade deficit comes from China, with which we currently have an almost $300 billion trade deficit.

There is no reason why we can’t be competitive in manufacturing, as many of the countries where we have the largest trade deficits in these areas—including China, Germany, Canada, Taiwan, Japan and Mexico—are countries we should absolutely be able to compete with.

But to do that, we must return to the kind of entrepreneurial efforts that made America a global power in the first place. We need to attack this challenge at the state level, with a particular focus on bringing manufacturing back to the U.S. Jobs are created in the states, not in Washington. The federal government can facilitate tax cuts, monetary policy and nationwide expenditure program—but it doesn’t create private sector jobs. And in particular, we need small and medium-size businesses to get involved, because they know best what is happening in their own states. They are closer to the ground and closer to the solutions. They need to get small groups of CEOs together to approach governors with the suggestion that the state’s economy can be stimulated by looking at that state’s unique products and services. And local government leaders will have a very personal interest in making this sort of plan work.

By bypassing Washington and putting the center of gravity in each state, we will effectively have 50 laboratories for experimentation and entrepreneurial activity around job creation. If we do this well, it will get the engine rolling and change the national psychology. Let’s stop waiting for Washington to deal with gridlock and come to the economy’s rescue. Instead, we can start using our initiative and creativity in the states and leverage the tenets of democracy to drive growth on a global basis. Then business will finally be seen accurately—not as another layer of the problem, but as a driving force for change and prosperity.

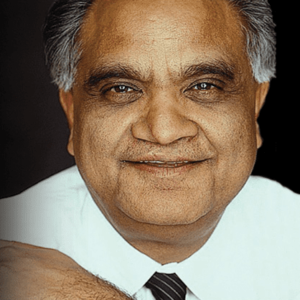

Ram Charan (www.ram-charan.com), 72, has been described by Fortune as “the most influential consultant alive.” Born and educated as an engineer in India, he received an MBA from the Harvard Business School, where he was a Baker Scholar. He taught at Harvard Business School and the Kellogg School at Northwestern University before becoming a consultant, strategic advisor and executive coach in 1978. A former director of Austin Industries and Tyco Electronics, he currently serves on the board of Hindalco. The India-based company is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of aluminum.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.