Of all the breaches created by the explosion in corporate cyber-security threats, the biggest one may be the “consequences gap”—the growing chasm between the fast-accumulating damage wreaked by online invasions of business data and CEOs’ frustrating impotence to stop them.

Just ask Sony CEO Howard Stringer, who created a bleak picture in May as he and the company reeled from cyber-sabotage against the PlayStation game network. Analysts believe this cost Sony about $1 billion in tangible damages and an incalculable toll in lost customer goodwill, tarnished brand equity and sleepless nights for the corporate brain trust.

“It’s not a brave new world; it’s a bad new world,” Stringer told The Wall Street Journal, with the apocalyptic mien of a CEO who couldn’t bridge the yawning cyber-sabotage consequences gap. “It’s the beginning, unfortunately—or the shape of things to come.”

Lockheed Martin CEO Robert Stevens, Fox Networks President David Haslingden and Michaels Stores CEO John Menzer also fell into the digital abyss in May when their companies were hit by major cyber-security breaches. In June, Citigroup CEO Vikram Pandit saw hackers access account information for about 1 percent of the company’s North American customers. Dozens of other CEOs have had to parry similar attacks, ranging from Bank of America’s Brian Moynihan—who saw the bank’s market value plunge in January just on the threat of an e-mail exposure by WikiLeaks—to Verizon CEO Ivan Seidenberg, Walgreen CEO Greg Wasson and Best Buy CEO Brian Dunn, whose companies were exposed by a major theft of e-mail data from the same Dallas-based outside marketing company.

Cyber-sabotage is a large-company problem, for the most part. Stealing intellectual property increasingly is the goal of data thieves the world over who tend to attack huge financial-services giants and other information-rich targets. And though defense, transportation and energy sectors have top-notch IT security, they tend to be frequent targets for cyber-saboteurs, who also might gain an opportunity through them to attack governments—including acts of cyber-terrorism. Yet, the most vulnerable private-sector entities remain those with treasure troves of customer and credit-card data that are susceptible to “old-fashioned” digital theft, especially companies in the retail, restaurant and hospitality sectors.

CEOTech Summit: October 18th and 19th at Stanford Business School

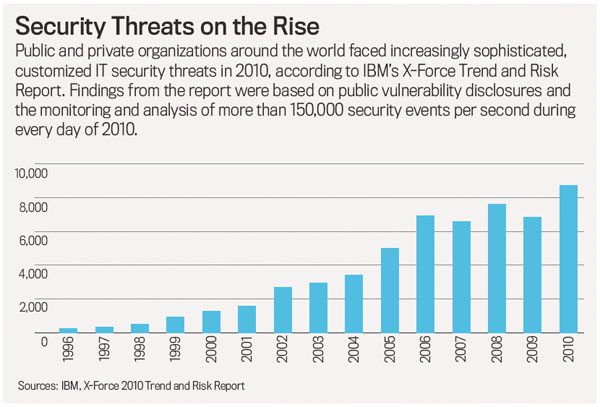

CEOTech Summit: October 18th and 19th at Stanford Business SchoolAnd the problem has become potentially overwhelming. More than 8,000 new cyber-sabotage “vulnerabilities” in private and public-sector operations around the world were identified last year, up 27 percent from 2009, according to IBM. And the brazen goals of data thieves’ attacks is growing as well as their quantity: About 25 percent of senior IT professionals in seven major countries told a McAfee Security survey that a merger, acquisition or product rollout had been “stopped or slowed” by cyber-sabotage or the threat of it.

“Staying ahead of these growing threats and designing software and services that are secure from the start has never been more critical,” says Tom Cross, threat-intelligence manager for IBM’s X-Force cyber-security service.

If you can’t be the fastest animal in the whole woods, at least make sure you’re faster than your friends,” so that the digital thieves first pick on other weaker members of your industry.

But while the challenge for IT departments is stark, not so obvious is what CEOs should be doing about this.

Despite the growing contagion of cyber-sabotage, the first problem with many chiefs is getting them to take it seriously. “There is a lot of lip service about making cyber-security a priority, but the rubber never seems to meet the road,” says Todd Thibodeaux, CEO of CompTIA, a computing-industry association based in Downers Grove, Ill. “Lots of CEOs just roll the dice. They figure they haven’t been hit yet, or at least in a hard way—and ‘the odds are we aren’t going to be.’ And other budget priorities come up. But damages are going to get bigger; regulations are going to get stricter. CEOs need to know how big a risk they’re taking.”

If cyber-sabotage finally has gotten your attention as a CEO— before or after an attack—here are five things you can do to narrow the consequences gap:

There are always other places CEOs can use their leadership capital. But the most effective corporate counter-attacks against cyber-sabotage are being led by CEOs. “Just as companies will rally around cost or quality-control issues, today it’s equally important to rally around security,” says Bill Edwards, chief information security officer for Vigilant, a Jersey City, N.J.-based IT-security concern. “And you need to be very visible with that commitment so that it permeates through the ranks.”

Perhaps set limited goals at first. “If you can’t be the fastest animal in the whole woods,” Edwards suggests, “at least make sure you’re faster than your friends,” so that digital thieves first pick on other, weaker members of your industry herd.

Put cyber-security visibly at or near the top of corporate priority lists. CEOs should push for systemic and “end-to-end” cyber-security that is well-funded and company-wide. They can also direct IT and HR departments to set up systems that classify internal data on the bases of the damage they could cause if disclosed, and on various levels of the “need to know.” And CEOs can prioritize comprehensive, mandatory training for all employees on cyber-sabotage prevention.

CEOs should make upper managers aware of their own vulnerabilities to attacks that exploit the behavior of strategically positioned individuals rather than involve a broad cyber-sabotage campaign. For example, in these so-called “social-engineering” maneuvers, data thieves may sit outside an executive’s home and tap into the household wireless network. C-suite executives can unwittingly expose their companies by sending sensitive attachments with e-mails or even by setting up Google Alerts for specific topics.

And in “spear-phishing,” criminals carefully wedge into corporate networks, sometimes over the course of months through a single well-selected victim whose e-mail, search or social-media habits can provide entry to the one PC required to infect or steal an entire information cache.

One of the big debates in cyber-security is whether prevention, or early detection and countermeasures, is the preferable strategy. CEOs naturally want to thwart all harm. But one problem with too much prevention is that it can interrupt the vital flow of data within a company, says Ted DeZabala, national leader of security and privacy services for Deloitte. Besides, cyber-criminals have become so sophisticated that “there’s a mind-set shift” by companies “from prevention to earlier detection,” argues Shane Sims, director of advisory forensics for PwC Consulting, and a former FBI agent. “You’ve got to transition your IT environment into an early-warning system.”

Another tough call for CEOs is when to notify authorities and customers in the event of a breach. Just three in 10 companies report cyber-sabotage incidents at all, McAfee estimates, because they don’t want to make customers and other constituencies worry, or to let hackers to know they’ve been proven vulnerable. “If your house has been burglarized,” as Sony’s Stringer puts it, “you find out if you’ve lost something before you call the police.”

Yet there are growing pressures on companies and CEOs to become more candid, more quickly, about cyber-sabotage. Certainly it’s something that customers want and expect. And there’s growing support behind a proposed federal law regarding notification of breaches that would supersede the laws of 47 states and broaden the types of data thefts that companies would be required to report.

CEOs can’t keep everyone happy, but they can try to limit the company’s cyber-sabotage exposure to staffers who become turncoats. Not surprisingly, Sims says, the most likely traitors are managers with access to important intellectual property or individuals with physical access to computer networks, especially senior IT leaders.

“A lot of people are still caught up in credit problems or mortgage difficulties and are financially desperate,” notes Sims. “It makes them easier to recruit by external groups.” Unhappy contractors, customers or partners can turn cyber-accomplices as well. Weak points often are small companies that supply large institutions, DeZabala said.

CEOs also should take the lead in visualizing the types of external threats who may be inspired to cyber-sabotage (see sidebar, p. 42) because of the industries a company operates in, or because of its specific political or ideological positions. The attack on Fox, for instance—which yielded personal information about hundreds of employees and contestants in the new fall show, The X-Factor—was claimed by group of hackers who wrote, “We don’t like you very much.” It wasn’t clear whether the hackers incorrectly believed they were attacking the Fox News unit of Fox.

“We see an increase in these types of activism-inspired attacks,” says Ilan Kinreich, chief operating officer of Radware, a cyber-security company based in Mahwah, N.J. “And they’re finding more ways to conduct their campaigns through cyber-sabotage.”

As digital technologies continue to proliferate, they create new potential conduits for cyber-criminal exploitation, and the best place for a CEO to get ahead of the game may be in these emerging areas. While experts believe that cyber-saboteurs have been relatively slow to exploit the security weaknesses of mobile-data networks so far, the rising number of smart-phone “apps” is providing them with opportunities that are too tempting to pass up.

But while many CEOs are wary of the corporate migration to “cloud” computing—basically, outsourcing of the operation of online networks—the truth is that “cloud environments such as those that Amazon and Google have are a much more secure environment than any that another company would be able to build on its own,” Thibodeaux says.

Sony’s Stringer hasn’t been alone in warning that the sort of cyber-criminals who hacked his company could increasingly turn their aim toward air-traffic-control systems, the power grid or the global financial system. But before he and other CEOs can protect the entire world from cyber-sabotage, they must do a better job of protecting their own companies.

CEOs know the faces of the victims of cyber-sabotage against corporations: Their employees, customers and partners. But who are the criminals behind all the digital sleight of hand?

“Picture an organized group of individuals whose sole purpose is to generate revenue by stealing from others,” says Bill Edwards, of security consultant Vigilant. “They run the gamut. They’re not all from a certain country or a certain economic class.”

But cyber-saboteurs do typically fall into one of the four categories:

Some foreign government intelligence services seek digital positions inside U.S. corporations to steal intellectual property as footholds in case of later national conflict. “They’re the most sophisticated cyber-threat, but the least likely to actually do any stealing,” says Shane Sims, director of advisory forensics for PwC.

Hackers who have formed loosely knit organizations across the globe are especially prevalent in China, Russia and the Ukraine, but also resident in Eastern Europe and Nigeria. These operators primarily want to steal information that they can convert to cash by thieving credit-card numbers or gaming stocks and commodities markets, for instance. Sometimes, they will demand ransom not to perform an act of cyber-sabotage. “This happens more often than people realize,” Sims says.

Digital theft and espionage by renegade companies is an inevitable outgrowth of the global economy.

“This threat group is the biggest,” Sims says, who notes that employees infiltrate systems for a variety of reasons. “Sometimes they do stuff themselves because they’re unhappy. Sometimes they look for an external sponsor from one of these other groups.”

Your CMO is begging you to start tweeting and to accept all those invitations to join LinkedIn. Your chief lobbyist thinks that writing a blog yourself would really score points on issues with politicians in Washington. And your spouse really believes your personality would come through if you shared more about yourself on Facebook.

But when it comes to your personal participation in social media, check with your chief security officer first. You’ll hear a different story.

Cyber-thieves love it when CEOs and other C-suite officers plunge into social media because it can provide them with the perfect openings to sabotage companies. “They don’t have to make a lot of digital noise on external-facing systems,” says Shane Sims of PwC. “They can go right for the jugular. It’s easier to target people and to trick them into sharing information that the thieves can use.”

Yes, you can individually express yourself via social media without risking the company jewels. “The key is how to embrace it without undue vulnerabilities,” says Kevin Kalanich, national managing director of Aon Risk Solutions. “Just make sure you have a policy of what you can disclose and what you shouldn’t. Don’t give out the keys to the kingdom.”

CEOs should be very wary of responding in the digital or physical worlds to questions that seem to stem from what they might have said in a Tweet or Facebook posting. “All the information [cyber-criminals] glean from these things can make it easier for them to pose as someone you might trust and get you to click onto something you shouldn’t,” Sims says. “Don’t do it.”

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.