After Cisco Systems announced a major strategic alliance with Itron on September 1, for establishing an Internet platform for the burgeoning “smart-grid” market for electrical utilities, the company didn’t waste any time finding complementary components. The next day, Cisco said it was acquiring Arch Rock, a privately held pioneer in—what else—smart-grid application.

he move was only the latest stemming from Cisco’s legendary knack for acquiring asymmetrically sized tech firms that become difference-makers inside their new parent. After nearly 150 rapid-fire deals over the last decade, voracious Cisco brazenly calls its acquisition strategy “best-in-world.” M&A experts far and wide agree, and note that the trailblazing company’s approach has created continual innovation as well as burgeoning scale.

“We’re constantly acquiring companies outside our sweet spot when there’s a market we want to enter,” said Ammar Maraqa, senior director of business development for San Jose based Cisco. “And we don’t think of mergers and acquisitions as a big event or a different process than our everyday business.”

Coca-Cola executives can only wish that their track record of “asymmetrical” acquisitions was so good. Rather than effectively leveraging such deals to tap into the most dynamic new segments of the fast-evolving global beverage market, Atlanta-based Coke is known for bumbling the ones it makes, ranging from its $4 billion purchase of Glaceau and the Vitaminwater brand in 2007 to the abandonment last year of its 23 percent stake in trendy Los Angeles-based acai-juice startup Bossa Nova.

“Bossa Nova should have been a great deal,” said Lloyd Greif, president of Greif & Co., a Los Angeles-based investment bank that brokered Coke’s initial investment in Bossa Nova. “But it didn’t work out because Coke didn’t have the experience to know what to do with it once they did a deal.”

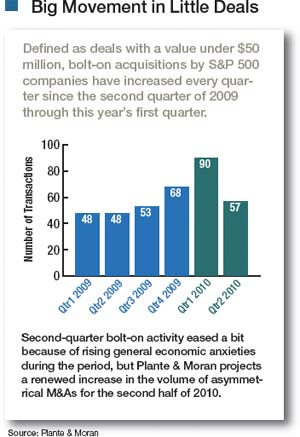

Asymmetrical acquisitions—typically defined as involving at least a 10- to-1 size ratio—always have been used much more frequently by the Fortune 500 than large, industry-consolidating mergers of equals or near equals. But the relative importance of small deals rose during the Great Recession, driven in part by the lesser perceived risk massive acquisitions represent.

“Credit markets are still tight for big mergers, and people remain nervous about the equity markets for financing too,” said Mike Bechara, managing director of Granite Consulting Group, Brewster, N.Y. “The stakes aren’t as high when you’re buying a smaller company.”

Large players also are finding better pickings because now even tiny companies can quickly leverage great ideas into groundbreaking products, new markets and even global dominance of a niche. Plus, every company is increasingly transparent to the wider business world because of digital media. The effect is Fortune 500 companies fishing in an amply stocked and brightly lit aquarium rather than poking around in a murky pond.

So, more big companies are loading up. Long known as an adherent of “not invented here,” for instance, over the last decade Procter & Gamble executed an about-face and has become a huge exponent of “open innovation,” meaning that it now constitutionally seeks outside ideas and products, opening its net to a sea full of potential small catches.

“We’ll look at a range of vehicles including acquisitions, joint ventures, equity stakes, or the potential to acquire a company,” said Jeff Weedman, vice president of global business development for Cincinnati-based P&G. “We take a look at what will best meet both companies’ needs and then consider almost an infinite variety of transactions.”

When it comes to outright purchases, said P&G CEO Bob McDonald, “the majority of acquisitions we do in the future will be bolt-on acquisitions” such as the company’s recently completed pickup of the Ambi Pur air-care brand from Sara Lee, for $470 million. “That took our [Febreze] air-freshener business from 15 to 85 [global] markets overnight.”

3M suddenly has become a huge believer in acquiring asymmetrical targets as CEO George Buckley tries to amp up growth. The St. Paul, Minn.-based giant recently boosted its commitment to spending on acquisitions this year to $3 billion, double the original designated amount—and exponentially more than the $69 million that 3M spent on acquisitions last year.

Intel also has turned into an active buyer over the last five years as it has expanded robustly into software. It made nearly $10 billion in acquisitions over the last year, especially in areas related to wireless connectivity. But in contrast to its Silicon Valley neighbor Cisco, Intel typically holds its acquisitions somewhat at arm’s length, keeping their revenue streams discrete and encouraging software startups to continue to serve non- Intel hardware customers as well.

“We become ‘chairman of the board’ but they’re still independent companies,” explained Renee James, senior vice president and general manager of the software and services group for Santa Clara, Calif.-based Intel. “It expands Intel’s capabilities without risking shareholder value.”

Asymmetrical acquisitions fall into two basic buckets. The first are bolt-on deals that add incrementally to an acquirer’s core capabilities. That’s what Malvern, Pa.-based chip maker Vishay Intertechnology did last year, for example, in adding to its measurements business by acquiring a small, U.K.-based company that gauges the weight of trash in garbage trucks.

“Transformational” transactions that help a huge acquirer move in the direction of fundamental change are the second type. Casket maker Hillenbrand Industries, for example, wanted to leverage its expertise in custom manufacturing of large metal goods into a strategic diversification. So the $650-million Batesville, Ind.-based company combed through 300 feasible candidates for acquisition before buying K-Tron International, a maker of material handling equipment, early this year.

“Their core competencies and culture are the same, so that won’t be disruptive, but this deal took Hillenbrand into a whole new industry,” said Scott George, managing director of the corporate-finance affiliate of Plante & Moran, a consulting firm that advised Hillenbrand.

Major players in asymmetrical acquisitions put out these guideposts for success:

Be strategic. Even small acquisitions must be part of the company’s fundamental strategy. P&G, for example, requires “an internal strategic owner and champion for the business” pushing for an asymmetrical deal, Weedman said. At Cisco, bite size deals “are the DNA of how we think about our business,” said Maraqa, “where the pace of innovation and disruption is tremendous, and Cisco itself is all about identifying and capturing market transitions.”

Occupy the same page. Make sure all the brass share an understanding about the importance of doing these deals, though some may be tiny. “Otherwise, there’s a tendency to think this deal is a ’rounding error’ and they don’t have to pay attention to it,” said Ron Ashkenas, managing partner of Robert H. Schaffer & Associates, a Stamford, Conn.-based advisory firm.

Move quickly enough. If a massive company wants to capitalize on new revenue opportunities, product innovations, or intriguing people by buying small players, they must move fast. Coke, for example, has rarely proved quick enough in this arena. It bought Glaceau at Vitaminwater’s peak—and just in time for a recession- induced fade.

“The beverage market is now changing so rapidly that if Coke waits to see what is going on in the marketplace, it becomes too late,” said Fariborz Ghadar, director of Penn State University’s Center for Global Business Studies.

Wade—Don’t Jump. As long as the overall strategy is moving forward, acquirers can be free to move deliberately.

The $100-million printer-software firm Monotype Imaging has moved gingerly in each of its three recent bolt-on acquisitions. “Each time we have started with some joint technical development and have seen what each other’s IP can bring,” said Doug Shaw, co-founder and CEO of Woburn, Mass.-based Monotype. “Then we had a handful of happy customers that validated [the combination] and we would say, ‘Do you want to join our company?'”

Anticipate—and then re-anticipate. Repetitive acquirers tend to figure out what they’re getting with asymmetrical acquisitions, but they can be surprised. New York-based online- marketing concern Seevast, for example, acquired domain-name manager Moniker.com in 2005 because their markets are naturally linked. “But the actual synergies were hard to come by because the new services weren’t necessarily something our clients needed—and they didn’t need it from us,” said Doug Perlson, Seevast’s CEO at the time. Seevast subsequently sold Moniker.com.

Serial acquirers also can underestimate the next acquisition. “Companies that have done a lot of absorptions think they can apply the same thing to the next one, but even repetitive types of acquisitions can turn out quite different,” said Gerald Adolph, senior partner in the mergers and restructuring practice of consulting firm Booz & Co.

Beware the contingent crowd. Bankers, accountants and others can tend to push CEOs into deals their companies don’t need because they don’t get paid unless it happens. “If you are looking for a deal, you’ll find one, because there’s a whole industry aimed at helping you find one,” said Mark Sirower, Deloitte Consulting’s lead M&A consultant. “So companies will walk backward into a strategy.”

Emphasize personnel. Cisco is a product- and innovation-driven technology company, but talent is a huge driver of its asymmetrical-deal selections. “Can we see the leadership team of this company become significant contributors and even leaders of Cisco?” says Maraqa. “IP in technology is tied to people.”

Darryl Ohrt was sold on dealing his small Danbury, Conn., marketing firm, Humongo Agency, to Norwalk, Conn.-based Source Marketing in large part because he was compatible with the CEO, Derek Correia. “We had worked hard to create an environment where employees had fun every day, and when I was doing business with him it was fun,” said Ohrt, who has stayed on to run Humongo. “It may sound like a minor point, but it was actually a key sign.”

And after a deal is done, of course, human sensitivities are the most crucial aspect of the last and biggest hurdle for creating successful asymmetrical acquisitions: integration. The enthusiasm of the principals and other key personnel of an acquired firm can be fragile, sometimes almost perishable. In fact, 90 percent of the benefits of integration are realized in the first 18 months—or they never happen at all, said Jeff Gell, global co leader of Boston Consulting Group’s M&A practice.

“Culturally there’s a challenge to make an integration strategy appropriate,” Sirower said. “But if the belief is that they need to be fully integrated, how do you do it without having the larger firm absolutely crush the smaller one in terms of bureaucracy and overhead structures that just aren’t appropriate for a small and growing entity?”

A big part of the answer is to regard the new help like family. “If you treat them like they’ve been conquered, they’ll rebel,” said Greif, the investment banker. “Don’t make people make choices that say you’re disrespecting them.” The right approach, he said, includes tolerating a newly rich selling principal who starts driving a Bentley even if the company car is a Cadillac.

More important than such subtleties, of course, is what an acquiring company does of substance to keep key personnel with their new property. Financial retention incentives for management and important salespeople often are called for. Intel creates “tracking stocks” so that at least part of the compensation of executives of the small companies they hire remains tied specifically to the performance of what used to be their fiefdom.

And savvy acquirers, large as they might be, also should continue to tap into the aspirations of the selling entrepreneurs. After all, in most cases they have kissed their independence goodbye not only for financial reasons but also because they believe the new “parents” can raise their offspring to become bigger and better.

“What I really wanted to be able to do was grow the company and take on challenges we hadn’t been able to take on before, and work on larger creative projects,” said Ohrt, of Humongo. “None of that requires ownership.”

Even Coke is trying to recalibrate its asymmetrical-acquisition strategy, in part by taking such concerns into greater account. Coca-Cola executives declined to comment for this story. But the company has formed a group specifically concerned about how to get involved with small, private brands and help them flourish— under the Coke banner— instead of stagnate.

“Coke,” even Greif conceded, “has learned its lesson.”

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.