In the pharma industry, a company’s future prospects are everything. One can only ride the wave of a blockbuster drug for so long before it goes off patent and generic versions edge in. But as anyone familiar with the rollercoaster-like road to FDA approval well knows, drug development is an expensive and extremely iffy endeavor. At any point along the process—from Phase 1’s early human studies and Phase 2’s efficacy testing on through navigating healthcare reimbursement programs—even the most promising compound can implode.

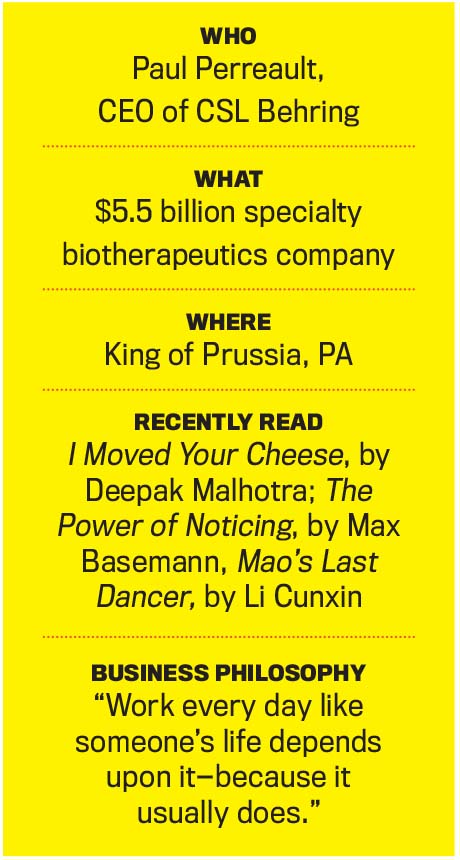

That’s a risk that pharma CEOs like Paul Perreault, CEO of CSL Behring, face regularly. “Our biggest business challenge is picking the right things,” he says. “It’s looking for those key items that you have insight into from a science perspective so that you’re not wasting R&D money, because that’s easy to do. You get enthralled with the neat stuff out there.”

In that sense, pharma is something of a microcosm for the broader corporate world, where intensifying global competition and commoditization have bred an “innovate or die trying” environment. At the same time, getting led astray by fear of being left behind or pursuit of the “next big thing” can be just as dangerous as inertia.

Thus far, Perreault, who took the CEO role at CSL in July of 2013, has avoided both fates, having successfully launched or registered (meaning introduced existing products in new countries) 22 new products around the globe in CSL’s last reporting financial year. Going forward, however, he has more ambitious innovation plans for the King of Prussia, Pennsylvania-based company, which makes plasma-derived and recombinant therapies for rare conditions like bleeding disorders and immune deficiencies.

“I want to look beyond the product and think about how we can innovate also the delivery and the infomatics that are being required in healthcare now,” he explains, noting that patient compliance is one of the challenges of treating children with hemophilia. Naturally reluctant to get a shot in the arm, kids who feel fine decide to skip their medicine. “If you can collect that information about compliance via a Bluetooth device and send it directly to the healthcare provider and the payers, you’ll have greater control over both the disease and management of

its cost. That’s innovation.”

Information is becoming a bigger piece of the innovation puzzle on other levels as well. For example, some new treatments have made it all the way through FDA-type gauntlets only to perish at the hands of insurers who refused to cover their use. “In Germany, there was a case where a new pharmaceutical that cost $200 million to bring to market was approved, but the governing body said ‘there’s no benefit over the current therapy so we’re not going to reimburse for it,’” explains Perreault. “To spend all that money and not have thought about how you’ll get it paid for is a huge mistake.”

To guard against that outcome, CSL focuses not only on developing new treatments but on gathering data to show a benefit over what’s currently available. “We have to get better at making sure we deliver the data to the regulators that justifies the cost of the medicines,” says Perreault. “All that work has to be done up front.”

At the same time, the company is continuing to develop new therapies. One promising area is a reconstituted high-density lipoprotein (RHDL)—aka good cholesterol—that will be used for patients who develop acute coronary syndrome after experiencing a heart attack. “From Hour Zero to Day 60 after a heart attack is when plaque is most unstable and you’re at the most risk of a second attack,” explains Perreault. “These molecules actually attract plaque from an affected artery and metabolize it through the body.”

CSL is also working to finalize its October 2014 acquisition of Novartis’ global influenza vaccine business for $275 million, a move that catapulted it into the big leagues in that business.

CSL is also working to finalize its October 2014 acquisition of Novartis’ global influenza vaccine business for $275 million, a move that catapulted it into the big leagues in that business.

Should the deal go through—it remains subject to regulatory approvals in a number of jurisdictions—CSL Behring will become the second largest-influenza vaccine manufacturing company, giving it economies of scale and strong pandemic capabilities in the U.S., UK, Australia and Germany.

But Perreault is quick to note that acquisitions won’t be the company’s principle growth strategy. “I looked at 200 possibilities last year; we did one,” he asserts. “We don’t acquire

things we don’t know anything about. That’s where companies get into trouble. They spend billions getting into an area and then billions getting out. When we do something, we do it in areas where we have expertise in it, adjacencies around it or the capability to improve it. I tell people that we do one big deal every decade because that situation is hard to find.”

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.