Dropping for decades, the typical tenure of a CEO is now between four and five years. In fact, business leaders in some industries only hold their posts for an average of two to three years. Given that a rocky leadership transition can have a profoundly negative impact on a company, this shrinking CEO tenure suggests that succession planning is more critical than ever.

Yet even large, well-run firms often fail to manage this crucial responsibility, Paul Winum, managing director and global practice leader of RHR International, pointed out to CEOs gathered for a roundtable discussion on CEO succession. “The absence of doing [succession] well has huge implications,” he added. “Apple’s Steve Jobs is a good example. His announcement that he was taking a leave of absence and introducing his second-in-command led to a 12 percent dip in the stock price.”

In fact, only 42 percent of directors rate themselves as effective on this critical aspect of their role, according to results of a recent survey conducted by RHR International and Chief Executive. And an alarming 48 percent say they haven’t seen a copy of the succession plan within the last year.

That disconnect reflects a simple fact: Succession planning is tricky involving multiple variables, demanding the support and involvement of both the CEO and board on an ongoing basis and presenting numerous potential pitfalls. What’s more, it’s downright unpalatable for business leaders who have no immediate desire to retire. After all, the task of developing an emergency succession plan involves facing the unpleasant prospect of stepping down for such disagreeable reasons as managerial shortcomings, health issues or even death. “There area lot of psychological challenges when it comes to something that could be viewed as planning your own funeral,” noted Winum.

In some cases the board must force the issue, pushing a recalcitrant CEO to formulate a succession plan. Some companies even withhold a portion of CEO incentive compensation if a viable succession plan isn’t put in place.

Bringing on the Board

Corporate boards are also often remiss about making succession a priority, reported Tom Wajnert, executive chairman of Alter Moneta, who reported serving on one board that found a creative way to overcome the inertia plaguing its succession planning process. “We called a special mock meeting with two days notice where we announced that the CEO had been lost in a plane crash,” he explained. “We spent two full hours in a simulation that had people really dealing with questions like: Is there a director who could sit in? Would we split the chairman and CEO roles? Who would be spokesperson? We made it a living experience for the board, and from there we were able to get their attention and launch the process.”

At AXA Art Insurance, a plan for handling that “lost in a crash” type of crisis is in place for every manager from the CEO on down. “It’s part of our global HR management rule that every leader every executive has to have a succession plan in place,” explains Christiane Fischer, CEO of the company. Fischer, however, saw identifying an individual as her successor as a virtual minefield. “For a company of our size, there is just not enough room for a designated successor,” she explained. “It could cause internal conflict or that person could get frustrated and leave. So I put in place a second tier of senior management that would function in the if-I-were-hit-by-a-bus situation. The team will run the company while a successor is being found internally or externally. A company should be in a position where it will be able to function totally and perfectly without the CEO for a given period.”

While acknowledging that the board holds significant responsibility for driving the succession process, several roundtable participants noted that identifying potential internal candidates and bringing them before board members ultimately falls to the CEO. “The person who knows best about internal candidates is the person sitting there now and doing a good job,” asserted Farooq Kathwari, CEO of Ethan Allen. “Their role is to get those people in front of board members and have them interact and spend real time getting to know and understand them. Otherwise, if a crisis hits, the board has two hours to make a decision—and will be making it again if they get it wrong.”

“The board needs to be exposed to the top five or six people who are most likely to be candidates for the top job,” agreed Bob Seelert, chairman of Saatchi & Saatchi. “Division heads should be making presentations to the board so that the board knows who all these senior people are. In the

Deep Development

Ideally, however, that boardroom exposure and the CEO succession process as a whole are an extension of a company’s human resource planning process. A good leadership development program actively looks for leadership talent four to five levels below the CEO for up-and-comers and routes talented people to positions where they can augment their skills and experience. “It has got to be almost simplistic,” says Bill Kroll, CEO of Matheson Tri-Gas. “If somebody at any level leaves, there is somebody else who will take over—just like in an army, where you were a major and now you are a general. That’s the kind of organization that one needs to create.”

Several CEOs pointed to GE as an example of a stellar succession process, noting that the company makes a practice of identifying potential leaders and ensuring that they get the experience and board exposure necessary to develop that talent. But other CEOs see a public GE-style horse race as potentially damaging. “To me the trick is to make sure that the majority of the race is invisible to the company and the constituents,” said Bill Mitchell, the former CEO of Arrow Electronics, who points out that GE’s succession practice only works at a company with its size and depth. “Most companies do not have the luxury to do that. What happens is by definition terribly destructive—people start speculating and in the latter stages you have people lining up behind candidates.” [Editor’s Note: Mitchell turned over the CEO job to his successor in May 2009—completing a planned transition he began on taking the post—shortly after this discussion took place.]

“The GEs and Citigroups are not real-world examples,” agrees Ed Smith, president of Barnegat Bay Capital. “The real world is the $1 billion or $5 billion companies, or the entrepreneurial firms, where most of these kinds of decisions have to be made.”

Managed poorly, succession planning can also lead to the loss of top talent, with newly trained leaders opting to secure a CEO seat elsewhere rather than patiently wait their turn at bat. “The process requires a very extraordinary, exquisite understanding of the people you have—their talents, capabilities, motivations, aspirations and all the things that drive their decision making,” cautioned Michael Kempner, CEO of the MWW Group. “While you are invariably not able to keep everyone, the more intimately you understand them, the better your ability to craft opportunities within the confines of the company that will maximize the likelihood that they will stay.”

At the same time, a certain amount of transparency – with the right successor announced at the right time – can help pave the way for a smooth succession, noted Winum. “If people don’t have visibility in the organization and confidence, they will spend their first month convincing people that they can do the job,” he pointed out.

Inside Out

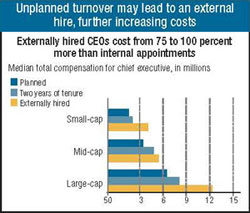

CEOs acknowledge that designating an internal heir and following a prescribed transition plan is generally preferable-leading to a smoother and less costly transition. In fact, RHR International research indicates that replacing a CEO with an outsider costs between 75 percent and 100 percent more than designating an insider as a successor. Yet, several participants pointed out that anointing an internal successor is not always feasible. Smaller companies, for example, may not have the resources to arrange for internal candidates to build skills and gain the experience a CEO needs.

Seelert, who took the helm of Saatchi and Saatchi at a time of turmoil and turbulence for the company, also suggests that in some cases bringing in an outsider can be the better strategic move. “[Outsider status] can be used to change the direction of the company in a positive way,” he noted. “If you use it as an opportunity, I would argue that an outside CEO can lead a necessary sea change for a company that is in chaos.”

Source: RHR International and Chief Executive magazine |

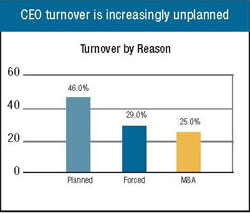

Source: Booz Allen Hamilton, CEO Succession Survey of 2,500 largest public companies globally, 2007. |  Source: Wall Street Journal. Data are for CEOs in the three major segments of the S&P 1500. |

Regardless of where the successor is found, the process should not end when a new leader takes the helm. “Often, we’ve found that at the end of the selection process the board takes a huge gulp of air, breathes a sigh of relief and says, ‘Thank goodness we found somebody’ and moves on,” said Winum. “But in fact it’s the next two years that end up being pivotal in terms of leveraging the opportunities or managing the risk associated with that transition. The post-selection integration process is really critical.”

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.