THE CHALLENGE

After parting ways with the pharmaceutical company you’ve led for three years and worked at for eight, you decide it’s time to build your own business. You pull together a three-page business plan, leverage a 30-year relationship with a venture capital company and launch your own pharmaceutical company.

THE CONTEXT

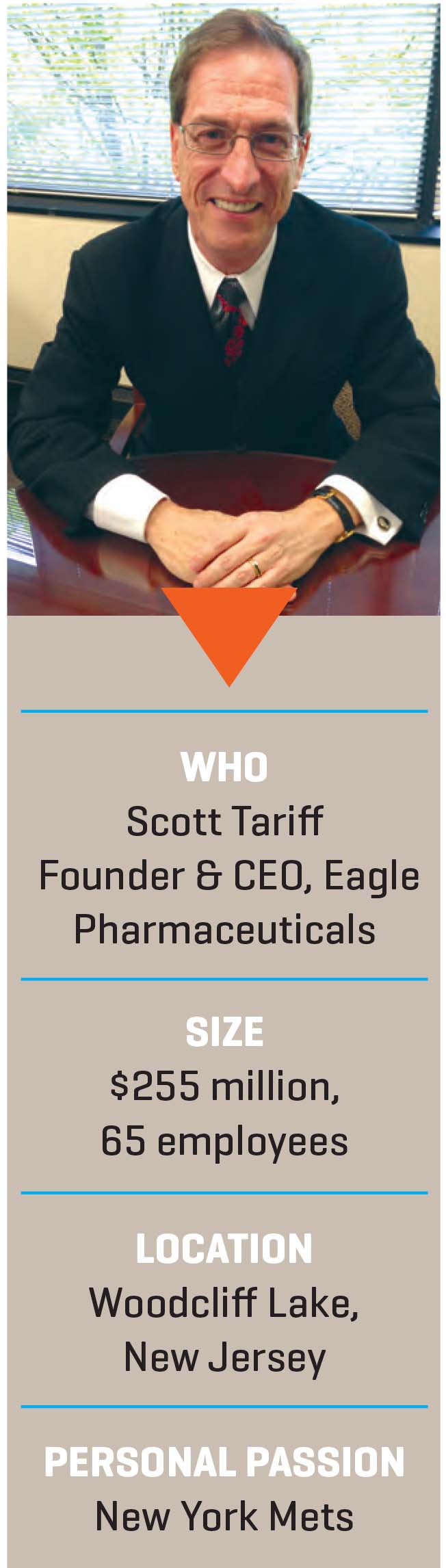

“Starting a business is not for the fainthearted,” says Scott Tariff, reflecting on the early years after he founded Eagle Pharmaceuticals in 2007. “We didn’t go straight up—there were a lot of days where we woke up with less than a month’s cash left in the bank wondering what the heck to do.” Working with limited resources demanded adaptability—and ultimately reshaped the company’s strategy.

Initially, Tariff intended to focus on generic drugs, a market he knew well, having previously led the generic drug maker Par Pharmaceuticals. In fact, his company’s moniker—in golf, a score of “eagle” is two strokes better than par—signaled Tariff’s intent to outpace his former employer. “They had their big sign on their building that said Par. I moved out and put up my big sign that said Eagle.” Soon, however, Tariff found his focus shifting to specialty drugs, a business originally intended to be a smaller sideline to the generic business. “We saw an opportunity and had to make a decision,” explains Tariff. “We basically flipped the ratio to more specialty drugs than generics.”

Tariff describes his products—primarily injectable treatments in the areas of critical care and oncology—as “line extensions.” Rather than developing brand new medications, Eagle talks to doctors, patients and nurses to identify problems with existing drugs and looks for ways to reformulates them to address those issues. Enhancing already-FDA-approved drugs enables the company to use an expedited FDA regulatory review pathway known as 505(b)(2), which speeds time to development and approval to market.

THE HURDLES

Reformulating drugs is a complex, expensive process that doesn’t always succeed—and that’s before factoring in the FDA approval process. Early on, and at a time when it could ill afford to do so, Eagle suffered its share of product failures. “When you are an R&D company and your R&D isn’t working, it’s a problem,” says Tariff. “We hung in there, learned from our mistakes, modified the products and ultimately wound up with some successes.”

Still, running a pharmaceutical business remains a risky undertaking. Just this past April, Eagle tussled with the FDA when the agency denied “orphan drug” seven-year marketing exclusivity for its lead compound, Bendeka. (An orphan drug designation is meant for drugs that treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people or for which there’s little hope of recovering R&D costs.) The agency’s surprise move came on the heels of a lucrative licensing agreement between Eagle and generic drug maker Teva, which was poised to market the compound as an improvement on its existing drug, Treanda.

In April, Eagle filed a lawsuit against the FDA protesting the decision. “It worked out in our favor,” says Tariff. “Teva is doing a great job transitioning their old formulation. I think we have 77 percent of the market share of [Treanda].”

THE ENDGAME

Today, the venture Tariff founded out of his home is a thriving company whose revenues are expected to hit $255 million this year. With growth has come stability, says Tariff, who took the company public in 2014. “The people we can attract today—as a successful public company—are different than the ones we were able to bring in nine years ago without products on the market,” he notes. “When you’re developing drugs you need the best formulators and developers. It’s all about the people.”

THE LESSON

Striking a balance between committing to your startup vision and being willing to consider the possibility of failure is tricky, but critical to success, says Tariff. “When you’re starting a business, you need to understand that there will be dark days before you get to the other side,” he says. “The key is to be honest with yourself about when to persevere and when to make significant adjustments or to move on. You can’t keep pouring money and time into a business that won’t work. On the other hand, you may just be going through a dark patch and, with perseverance, you’ll come out the other side.” Most company founders need help navigating the twists and turns in the journey, he adds. “Everyone needs mentors,” he says. “You need to surround yourself with talented people who you can trust and listen to in order to help you be objective about how to move forward.”

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.