While driving gender and ethnic diversity among directorship roles has gained traction at large, consumer-facing companies, movement has lagged across corporate America as a whole. Yet a growing body of research suggests boosting diversity in your boardroom is worth considering.

If you’re the CEO of a consumer products company, it’s not hard to make a case for diversity. After all, the market you’re after is more heterogeneous than ever, so strategically it makes sense to have an executive team and a board that reflects that mix of cultures, genders and ethnicities.

But what if you head up an industrial B2B company? Does pursuing a more diverse board do anything more than show the world you’re keeping up with 21st century social trends? Given how few sitting CEOs are women and minorities, does this mean you should abandon a long-standing strategy of seeking out experienced CEOs to serve as directors? In principle, you might agree with the value of a diverse culture. But in practice, does it make sense for your business?

“The role and responsibility of the board is to the shareholder, and the shareholder doesn’t care about diversity,” says Paula Cholmondeley, CEO of The Sorrel Group, a director education consultancy. “They want the best ‘team’ that can deliver and enhance the value of the organization.” Cholmondeley would know; she has served on eight corporate boards and on just about every committee, as well as held senior financial and strategy positions at a variety of large companies, including Owens Corning, The Faxon Company, Blue Cross of Greater Philadelphia and Westinghouse Elevator Company.

In her view, diversity isn’t something you seek because you want the positive PR or because it’s the nice thing to do, but rather, because you want to fill out the mix of skills the company needs in the boardroom to succeed in its mission.

“The fallacy that has, I think, turned into a belief and is wrong is that the only team or the best team to produce results is a team of CEOs,” she says. “But companies don’t run based on teams of CEOs, and a CEO doesn’t surround himself with duplicates of himself. Every corporation that excels at anything is structured to bring a multiplicity of topical skills to the team.”

Boards, too, need a multiplicity of skills. Regardless of the type of company or the industry in which it operates, a lack of diversity in the boardroom—based on gender, ethnicity, age, background, nationality, etc.—could hurt, even if everyone sitting around the table is a CEO. “The stronger boards are composed of a mixture of CEOs and of people with senior functional skills, which will vary based on the company and the industry,” says Cholmondeley, noting that contrary to long-held tradition, previous board experience shouldn’t necessarily be a prerequisite. “Once you say you want a senior functional skill, you’re not talking about the CEO.”

While many companies have embraced this point of view, others feel that they can’t afford to prioritize diversity in the boardroom and/or question the business case for doing so. Yet a growing body of research suggests that diversity at the top correlates with greater innovation and success. A global study by McKinsey & Co. found that returns on equity for companies ranking in the top quartile of executive-board diversity were 53% higher, on average, than they were for those in the bottom quartile. EBIT margins at the more diverse companies were also 14% higher, on average, than those of the least diverse companies.

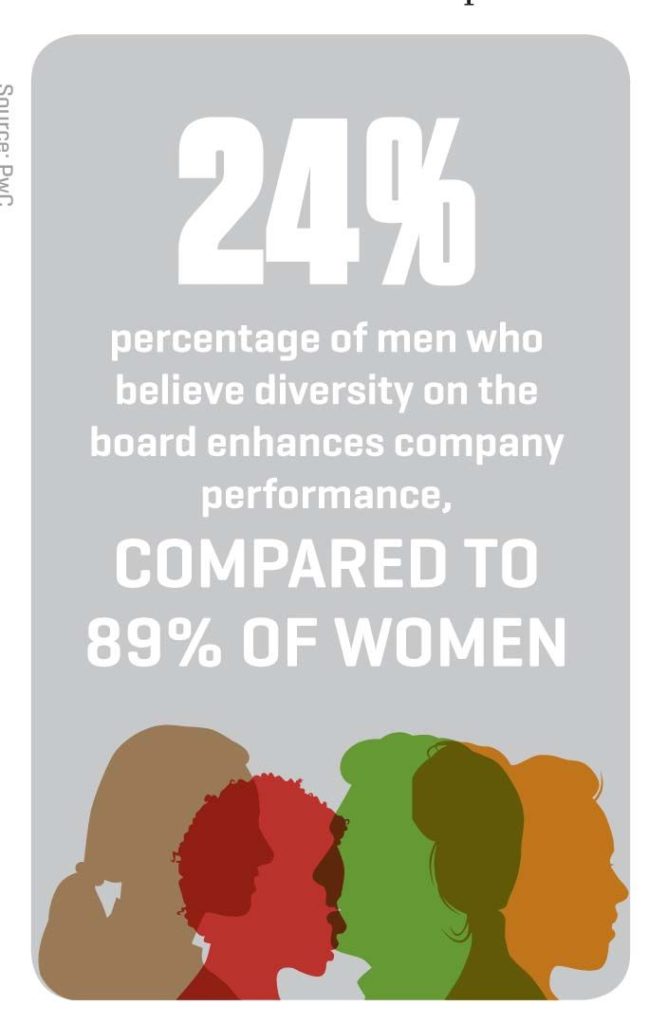

Another study by the Center for Talent Innovation found that employees at companies with more diverse leadership were 45% more likely to report that their firm’s market share grew over the previous year and 70% more likely to report that the firm captured a new market. And consensus around the sentiment that boardroom diversity matters is building among business leaders. In the 2016 update of its governance principles, the Business Roundtable strongly endorsed a link between racial and ethnic diversity in boards and board effectiveness and the creation of long-term shareholder value.

Given the growing body of evidence, few companies, even B2B, industrial, non-consumer-facing manufacturers, can afford to ignore the growing diversity of workforce and consumer populations, asserts Idalene Kesner, dean of Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, who spent many years researching board diversity in the ’80s and ’90s.

“I would say there are very few industries today that aren’t touched by the need to be responsive to our diverse population,” says Kesner, who sits on the board of Berry Plastics, a global manufacturer of packing solutions. “One of the things Berry does is design containers. If you can imagine, at the most mundane level, a container that fits a woman’s hand or a container that’s more appealing to various diverse groups—that definitely has sales implications to it.”

Ronald C. Parker, president and CEO of The Executive Leadership Council, agrees, adding that the customers of B2B companies are looking for diversity in their vendors. “They’re now insisting that the reps who call on them look like the population they serve.”

Companies like DuPont, MasterCard, Coca-Cola, Ford, P&G and The Walt Disney Company have all taken steps to actively engage diverse suppliers. As DuPont pledges as part of its formal commitment to maintaining a diverse supply chain: “Ensuring our supply base reflects our customers, employees and the communities where we live and work is a key business strategy.”

Making it Happen

Despite this building momentum, progress on moving the needle with boardroom diversity has been sluggish. According to a study by Deloitte and the Alliance for Board Diversity, women and minorities held 30.8% of Fortune 500 boards seats in 2016—up from just over 25% of board seats in 2012. When compared with the exclusively male, all-white boards that once held the lion’s share of boardrooms in Corporate America, that’s a significant change. But compared with the fast pace of changing demographics in the U.S.—and noting the fact that women make up over half of the consumer population—some argue women and minorities are still significantly underrepresented.