In his classic work, Management, written 40 years ago and arguably still the best book on that subject ever published, Peter Drucker wrote “What differentiates organizations is whether they can make common people perform uncommon things.” Drucker would later identify people decisions as among the most important ones a CEO makes because they determine the performance capacity of the organization. “The only thing that requires even more time and work than putting people into a job is unmaking a wrong people-decision,” he added.

Since 2005, Chief Executive has partnered with a professional services firm to study the leadership development capacities of companies, then ranked the top 20. In a break with the past, CE decided this year to take the research to another level, in part to differentiate its rankings from others, but also to get a richer understanding of what companies do to develop leaders several layers below the CEO. In partnering with Chally Group Worldwide, a leading management and sales-force research firm, we were able to conduct a more rigorous methodological study.

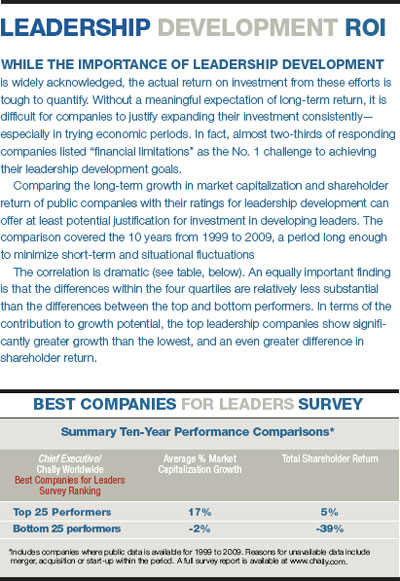

The evaluation method established multiple qualifying criteria. These included the existence of a formal development program, the percentage of time the CEO is personally involved, the percentage of both senior leadership and middle management recruited internally, the frequency of being cited as a recruiting target by other organizations and the long-term growth of market capitalization. This last criterion, while only a smallweighting, makes a substantial difference in the rankings, elevating the status of some less-familiar names and diminishing the rankings of some better known icons. For example, in the initial years GE and P&G consistently ranked first and second. In 2008, 3M broke the monopoly and ranked first. This year, P&G retains its silver status, but GE drifts further back, not because its process has deteriorated— most companies would covet its Crotonville education center—but because its decline in market cap can hardly reflect a decent return on the quality of leadership. In the end, company performance should mirror the quality of the leaders it has developed.

JPMorgan Chase powered over many of the usual suspects to finish on top. The financial giant has a well-established internal program to develop world-class talent. Its structured leadership pipeline incorporates broad experience across its full range of product and service lines. The skills and experiences include structured rotations, career planning and coaching, and continual training and development. The company’s program incorporates a wide range of competencies, from strategic planning and P&L management to international experience and new business development.

In speaking to 2009 Harvard Business School graduates, CEO Jamie Dimon outlined 11 attributes central to leadership, many of which are embedded in his company’s development philosophy. A few are worth highlighting:

Discipline: “You have to be very disciplined. That means rigorous, detailed meetings and follow-up. You have to do it consistently. It’s like exercising or weeding the garden—you don’t get there and stop. You have to have a strong work ethic. And you have to be always striving for improvement.”

Standards: “Standards are not set by Harvard Business School or the federal governments of the world; they are set by you. You have to set high standards for performance. If you don’t, you will fail. Always compare yourself to the best in your industry at a very detailed level and analyze why you’re different.”

Face facts: “Look at the facts in a cold-blooded, honest way all the time. At management meetings, emphasize the negatives. What are we not doing well, how come the competition is doing better? People say I focus on little things about how we allocate expenses. It is not a little thing.”

Openness: “What you want is full sharing of information, then a debate about the right thing to do. The job of a leader is not to make a decision; it’s to make sure the best decision is made. To do that, you need to get the right people in the room.”

Loyalty, meritocracy and teamwork:“When I was a young CEO, someone said, ‘We love the company, but you demoted Joe. How can we be loyal to you when you’re not loyal to Joe?’ Yes, we demoted Joe. And Joe was a pillar of society and a wonderful person. But Joe was no longer doing a good job. If we were ‘loyal’ to Joe by leaving him in that job, we would have been hugely disloyal to everybody else and the clients of the company. That, right there, is the hardest job you are going to face.”

Respect: “Treat all people properly and treat everyone the same, whether they’re clerks or CEOs. Treat everyone equally and with respect. And promote people who are respected. Would you want your child to work for that person? If not, you really should question why you would allow that promotion to take place.”

Procter & Gamble is to leadership development what the 1927 Yankees are to baseball. To be a “Proctoid” is to be Major League. More than 99 percent of its senior leaders were produced from within the Cincinnati-based company. (Less than 5 percent of its later-stage hires come from outside.) The majority of individuals within P&G have been trained and promoted from an entry-level position. Many P&G alumni have become highly successful elsewhere: More than 120 are current or former CEOs/chairmen, including the CEOs of eBay, Clorox and Intuit.

“The single most enduring thing P&G leaders can do is to identify and develop our next generation of leaders. If we can get the right people with the right skills and experiences in place to run our business, the rest will take care of itself.” says Laura Mattimore, director of leadership development. The company believes in the continual education of people at all levels. Even its most senior leaders participate in learning events to sharpen their skills. Most courses are taught in-house by experienced P&G line managers. Even the CEO tries his hand.

The company maintains a comprehensive database of its 138,000 employees, a massive constellation whose stars are tracked carefully through monthly and annual talent reviews. In these sessions, Proctoids discuss their business goals, their ideal next job, and what they’ve done to train others. When a position opens, the company can readily draw upon a list of employees who are ready to move immediately to, say, an Eastern European country, complete with their performance reviews.

IBM’s rank among the top five also promises to be secure, as its people initiatives have many imitators, and not without reason. Potential leaders across the company are assessed annually against 11 competencies, as are all IBM’s executives as part of the company’s succession planning process—which relies on the premise that real development happens on the job through experiences.

According to Donna Riley, IBM’s vice president of global talent, “It’s not about creating lists of people who can do something someday. It’s about finding very talented people, letting them know that we found them and value them, and then providing them with mentoring and the rich and varied experiences to move them towards a higher level of responsibilities.”

Experts say Big Blue is charting new territory by combining the international, community-service and leadership development pieces in a single program. The company selects 100 rising stars and groups them into teams. Each will spend a month in one of six developing countries, living and working with local companies, governments and organizations. Big Blue also formed a new initiative called the Center for CIO Leadership, a global community of executives and academics focused on developing CIOs and advancing the profession as a whole. The center is headed by Harvey Koeppel, with a governing council comprising CIOs and professors from MIT, INSEAD, Harvard and other institutions.

With two Indian corporations finishing among the top five, and five among the top 40, it’s fair to say that companies from the subcontinent are serious players in developing human resources—with revealing differences in approach. For example, U.S. and European companies tend to view strategy-setting as the sole province of the CEO and the senior team. By contrast, Indian companies tend to view it as a group-wide exercise involving managers at levels considered somewhat junior by U.S. standards.

Bangalore-based Wipro marks its strategy to build leaders through internal and external education, from entry level to senior executive, along four key bands. Each job within a band is clearly outlined for building discrete competencies that will ease career movement. This is geared to creating a 9,500-member organization where learning and leadership development is a continuous process. (There are 300 professors on staff at Wipro University, most of whom are paid more than their counterparts at Indian universities.)

Bharat Petroleum fosters value-based processes for development that focus on competencies and capabilities designed to place the right person in the right job. The company puts 3,000 people through two management programs at its training center in Mumbai’s posh beach neighborhood of Juhu to help give them a competitive edge, as well as helping Bharat to spot gaps and find right leader for the right job.

Like Olympic downhill skiers or track-and-fielders, the leading 40 companies cited here are separated in their final scoring by slim margins— the equivalent of tenths of a second. All are champions of leadership development.

SelectIng 40 of 1,300 respondents as the “Best Companies for Leaders” involved a multi-step process based on the CEO’s and company’s commitment, methods and results.

First, companies responding to the survey were scored on key criteria including: 1. Having a formal leadership process, 2. The commitment level of the CEO, as measured by the amount of time spent personally involved with the leadership process and developmental program, 3. The depth of the leadership funnel as measured by the percentage of senior management positions filled by internal candidates as well as the percentage of middle management positions filled by internal candidates, 4. The number of other responding companies that recruited from the company being evaluated.

Because it would be inappropriate to compare smaller businesses with global giants, the list was then narrowed to those either with more than $1 billion in revenue or those listed as Global 1000 largest companies.

To this narrowed list, a fifth criterion based on increasing shareholder value was factored in. The 10-year change in market capitalization (where available) was converted to modifications in point totals based on the growth or decline in market capitalization during the preceding 10 years. For companies where comparable data did not exist as a result of changes in capital structure or of merger or acquisition, points were added or reduced based on the overall average, which had minimal effect on the initial ranking for those organizations. To balance out the advantage smaller companies had by using a percentage of market cap growth, the actual market cap increase or decrease was also converted to add or subtract points. The final list was a composite of these two internally reported and externally reported sources.

The effect of these financials was dramatic for some. For example, GE ranked highly on internal criteria, but dropped substantially based on having lost $300 billion-plus in market cap and experiencing a -69 percent return on its stock price, at the outset of the measurement period. The effect on Intel, the other major anomaly, which lost more than $70 billion in market value and provided a -58.6 percent return, dropped it out of the top 40 altogether. However, these are extreme outliers in terms of financial performance. With few exceptions, the companies top-rated on commitment and methods only moved in small increments due to financials. The same was true for the bottom-ranked companies. This reinforces our findings that placement in the rankings is somewhat trivial within the same broad bands.

This helps explain why lists of only 20 or 25 “top-ranked” companies can vary so much across different surveys purporting to measure leadership. It also explains why a company’s rating can change significantly in the space of a year, even from the same research source. If the Chief Executive/Chally Group Worldwide’s list were expanded to 100, it would include virtually all those listed on both the shorter Fortune and Bloomberg BusinessWeek lists. Like the Olympics, the difference between 1st and 15th is incredibly small and is likely even to be incidental. The principles of total quality management (TQM) should apply here. Use the lessons from any or all of the many at the top…to avoid being less than adequate.

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.