Alex Schulze is a poster boy for millennials: an entrepreneur who plays to the unmatched environmental sensibilities of Generation Y. The 27-year-old Floridian co-founded 4Ocean, which pays Pacific fishermen to collect plastic ocean waste that the enterprise makes into bracelets and sells for $20 apiece.

Alex Schulze is a poster boy for millennials: an entrepreneur who plays to the unmatched environmental sensibilities of Generation Y. The 27-year-old Floridian co-founded 4Ocean, which pays Pacific fishermen to collect plastic ocean waste that the enterprise makes into bracelets and sells for $20 apiece.

“It’s really a movement that we created a business around,” says Schulze, whose company stands to rake in about $50 million in its first year of operation.

But wait, maybe Stephanie McGuire is actually the face of the millennial generation. A 34-year-old legislative analyst with a one-year-old son, she and her 30-year-old husband recently moved from downtown Lansing, Michigan, to a two-story house with a yard and a white front porch in suburban Diamondale.

“Buying a house might be a dream delayed for a lot of millennials because of student debt and what the economy was,” McGuire says. “But that’s what a lot of my friends are doing once they have children.”

CEOs have long known how much is at stake with the most populous demographic cohort in American history, a collective 70-million-some shoppers born between 1981 and 1996, according to the Pew Research Center.

Some iconic companies have hit the shoals in large part because they’ve wrongly assessed millennial consumers. Harley-Davidson hobbled U.S. sales with an inability to lure enough millennials. Procter & Gamble is struggling with CEO David Taylor’s strategy of focusing on its huge existing brands over smaller, newer ones that millennials favor. And even amid a retailer renaissance in 2018, enfeebled JCPenney is flailing thanks to new clothing lines that don’t appeal to millennial women. Campbell Soup tried to bait millennials with soup in pouches and in zesty new flavors, but CEO Denise Morrison was ousted last summer in part because she couldn’t overcome the company’s association with traditional table fare in the minds of Generation Y.

“Millennials are buying bone broth in shelf-stable boxes because they think the products are better,” says Ken Harris, a long-time CPG advisor and managing director of Cadent Consulting. “Soups are doing just fine; but Campbell isn’t.”

But other companies are prospering in large part because they’ve figured out Gen-Y. Nestle is selling them the new Wildscape frozen meal-bowl brand, and startup Rind is peddling dried fruit pieces with the skins on. Ford is moving mammoth, $50,000 Expedition SUVs to millennials, while Thor Industries is getting them into recreational vehicles.

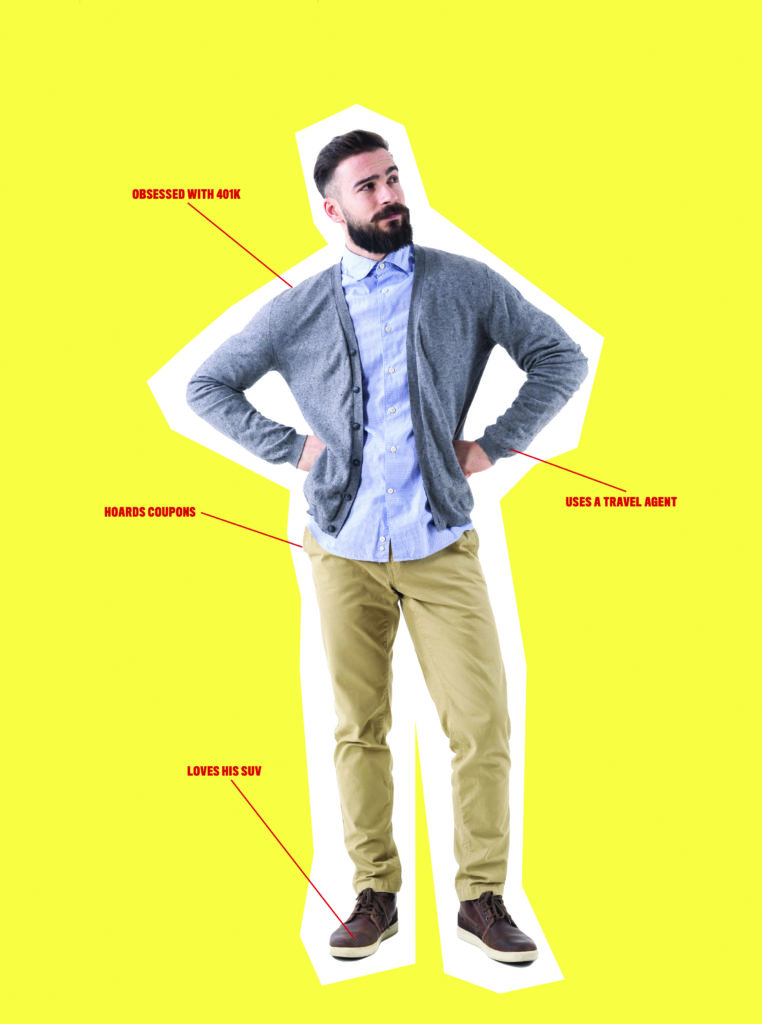

Why such varying track records? While of course millennials’ attitudes and behaviors range widely, some huge myths have grown up around their tendencies and values—the biggest of them being that millennials are unique.

“There are important differences between generations, for sure, but millennials and boomers are more alike than any of the other five generations in North America right now,” says Sheryl Connelly, Ford Motor’s futurist.

Richard Dix, CEO of home-builder Winchester Carlisle, believes that “millennials are acting very much like their parents—just in a dramatically delayed way. Their front-end life stages are much more elongated than [boomers’] were. When they take that next step and get married they tend to fall very much in line with what we look at as traditional behaviors.”

Winning CEOs in the coming decade will be able to separate fact from fiction about Generation Y and act accordingly. We examined some conventional wisdom about millennials, and found examples of how companies are making some of the right—and wrong—bets:

Just as a 72-year-old boomer is far different from a 54-year-old boomer, a freshly minted college graduate doesn’t have a lot in common with a father of three kids who’s pushing 40 and has been in his career for 15 years—though both are millennials. And how they grew up may have exacerbated some of those differences.

“Someone in that first five to seven years of the millennial generation has a lot more in common with [older] Generation X than with a 25- or 26-year-old,” says James Rigney, Thor’s senior director of marketing. “So your marketing needs to double down on their particular life stage.”

Also, Generation Y was “split right down the middle by the financial crisis of 2008,” notes Ford’s Connelly. Visa Chief Marketing Officer Mary Ann Reilly adds, “You need to break them into older and younger. Older ones are more like their parents, and that really may be more of an age thing and where they’re at in their lives. They begin to have more similarities to older generations. But millennials who are 28 or younger, there’s a question whether they’re changing that way.”

Chief Executive Group exists to improve the performance of U.S. CEOs, senior executives and public-company directors, helping you grow your companies, build your communities and strengthen society. Learn more at chiefexecutivegroup.com.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.